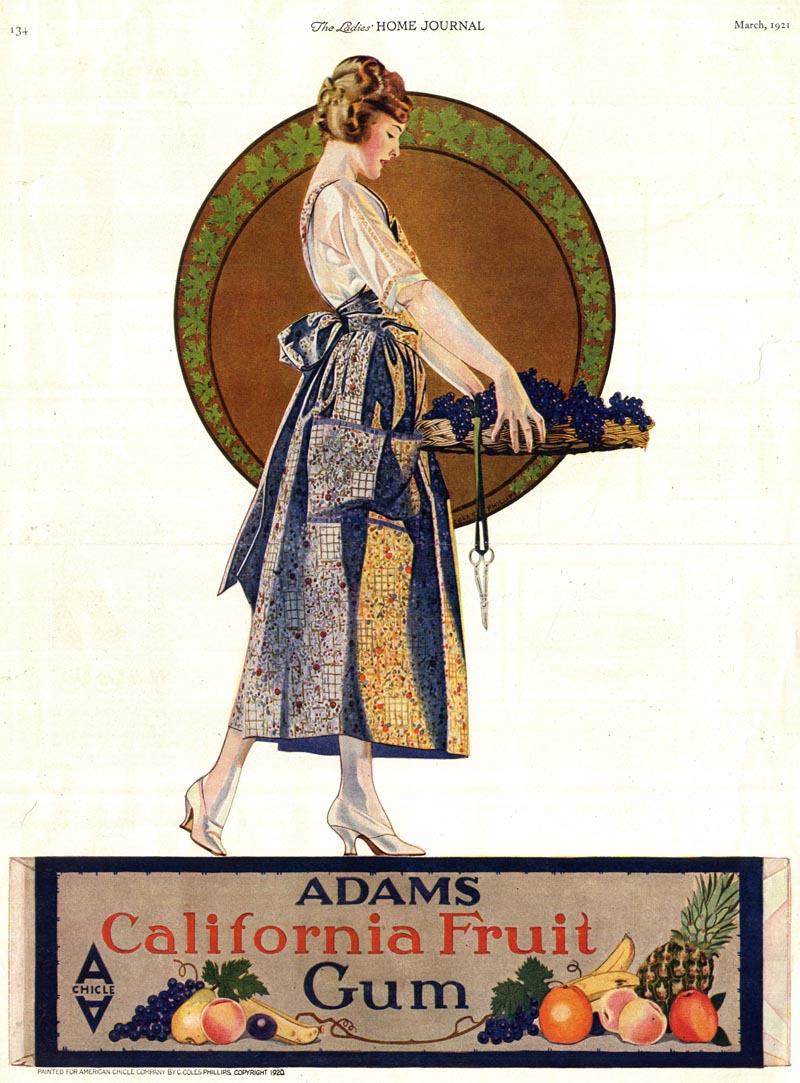

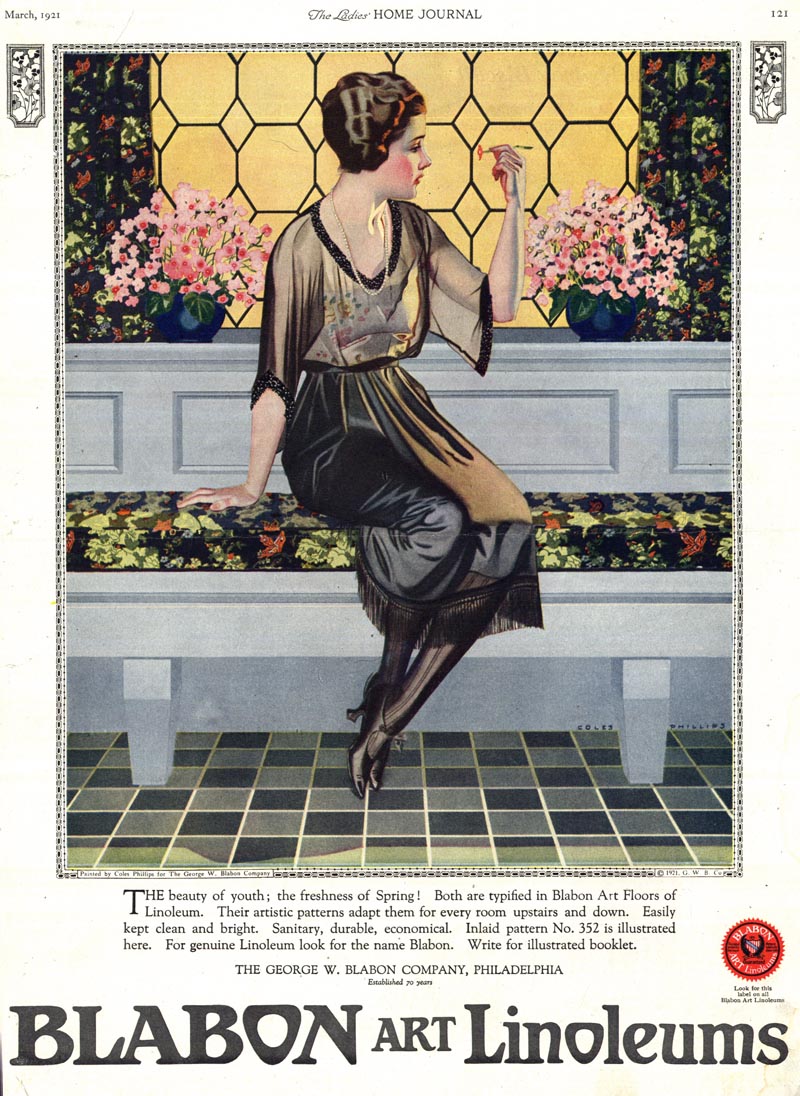

"Coles never painted anything but pretty girls. He used to get marvelous prices for his work, as much as, if not more than, any other illustrator."

"First he'd think of the best price he could hope for; then he'd think of his four children and add four hundred dollars. In the twenties he received two thousand dollars a picture, which was fabulous."

"Coles didn't decide to be an artist until he'd finished college. And he'd already decided that he was going to make a hundred thousand dollars before he was thirty-five. As he was a very smart fellow (I always felt he would have risen far whatever line of work he'd chosen), he did become an artist and he did make a hundred thousand dollars before he was thirty-five. (And he married a very beautiful girl, too)."

Using our handy inflation calculator we can quickly determine that Coles Phillips made over 1.2 million dollars from his art before he was thirty-five. His 1920s illustration fee of $2,000 would be over $23,000 today.

At that same time, Norman Rockwell was himself beginning to earn some very decent money. He describes one ad campaign he began in 1921 - a series of twelve paintings for Orange Crush - which paid him $300 per painting. While nowhere near the kind of money Coles Phillips was earning, it was a very good fee at a time when the average family income was only about $1,200 per year. "It seemed like such a lot of money that I couldn't resist." wrote Rockwell. And Orange Crush was only one of his advertising clients at that time. He was also receiving assignments from Willys Overland car Company, Fisk Bicycle Tires, Coca-Cola and Jello.

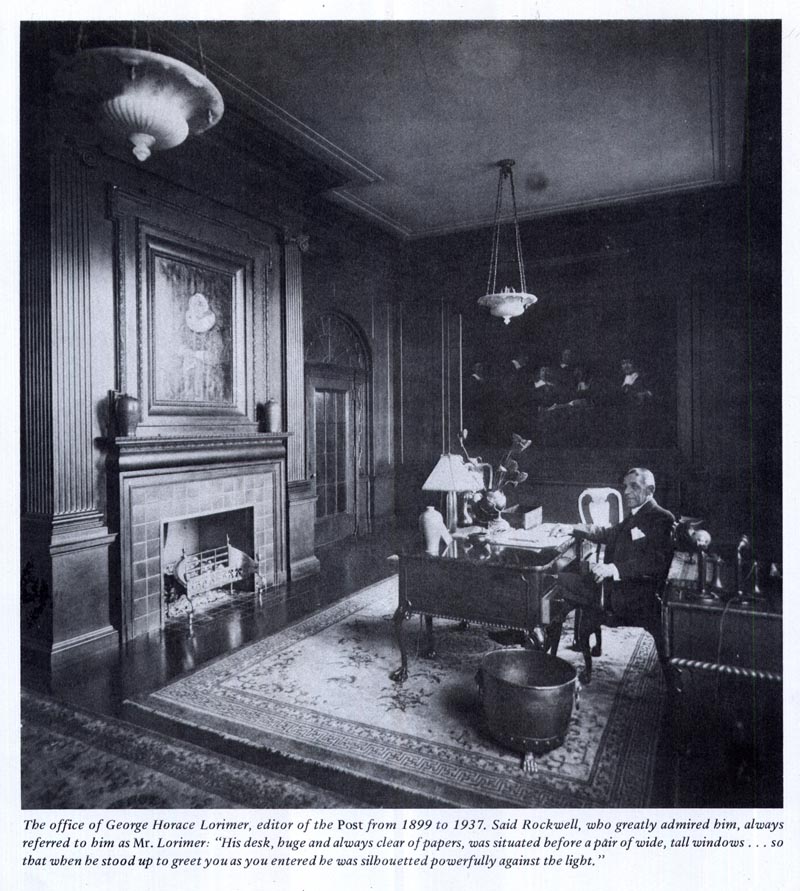

Besides all this ad work, Rockwell was doing magazine illustrations and covers for many magazine clients, most famously for George Lorimer, the legendary editor of the Saturday Evening Post (shown at his desk below).

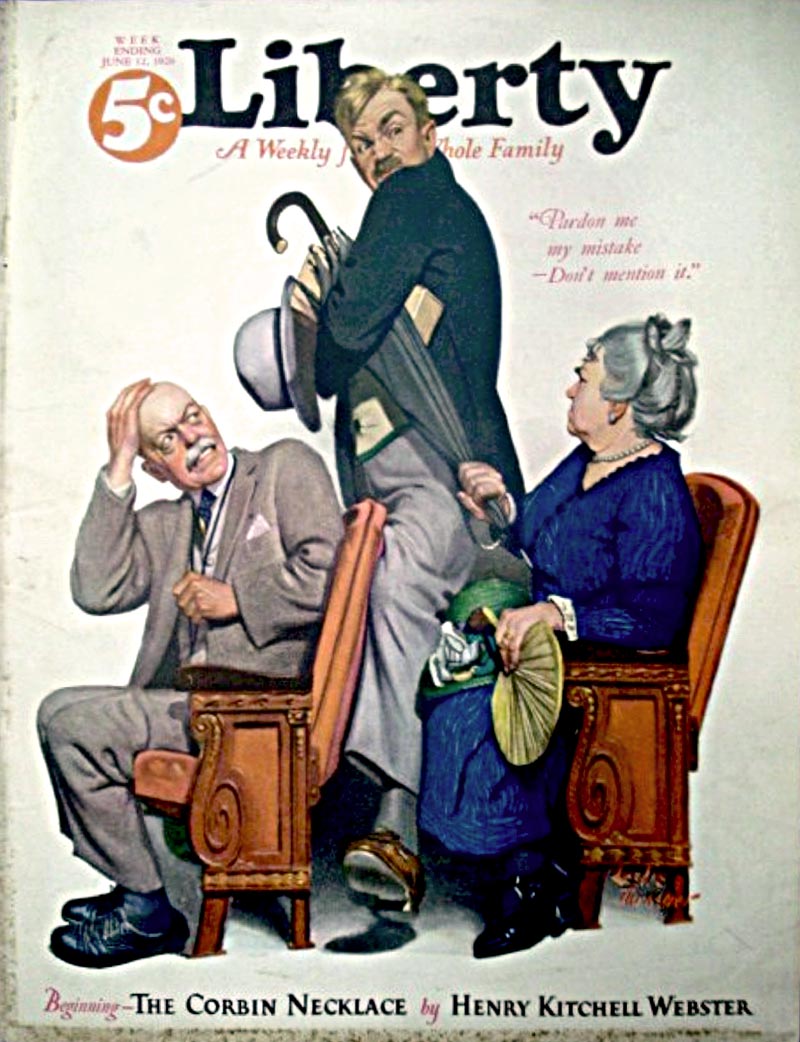

In 1924 the art director of Post rival, Liberty magazine, came to Rockwell's studio to offer him double the fee he was getting at the Post if he would jump ship. Because of his strong sense of loyalty to Mr. Lorimer, Rockwell refused. But his wife insisted that he confront Mr. Lorimer and insist on a substantial raise. Rockwell had been illustrating covers for the Post for eight years at that point and his fee, $250, had never risen more than nominally. When Rockwell visited Lorimer and described the situation with Liberty magazine's offer, Lorimer doubled his rate. He also advised Rockwell to charge his advertising clients twice his Post cover rate.

Its not surprising then that, at a time when the average annual family income was just over a thousand dollars, Rockwell describes being able to put ten times that amount into savings in a matter of months.

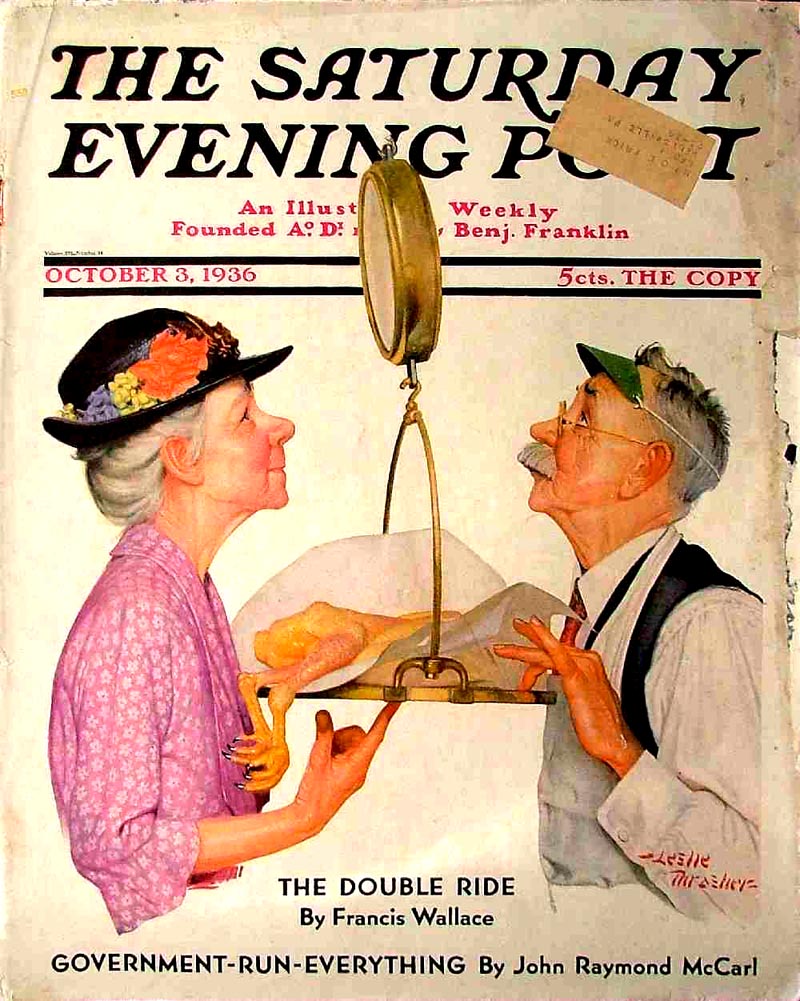

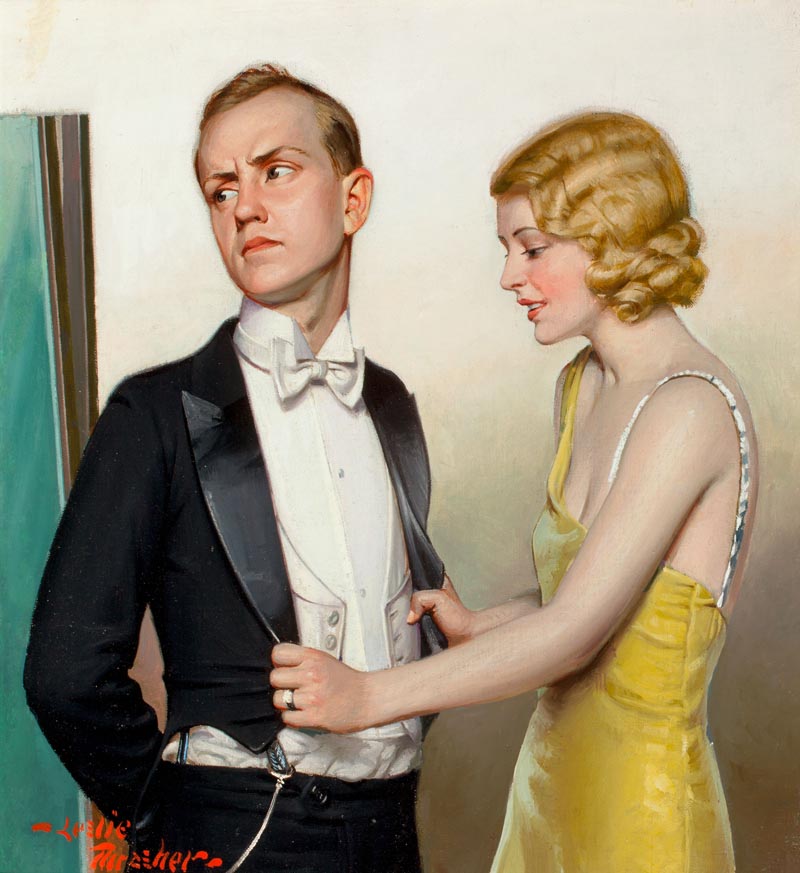

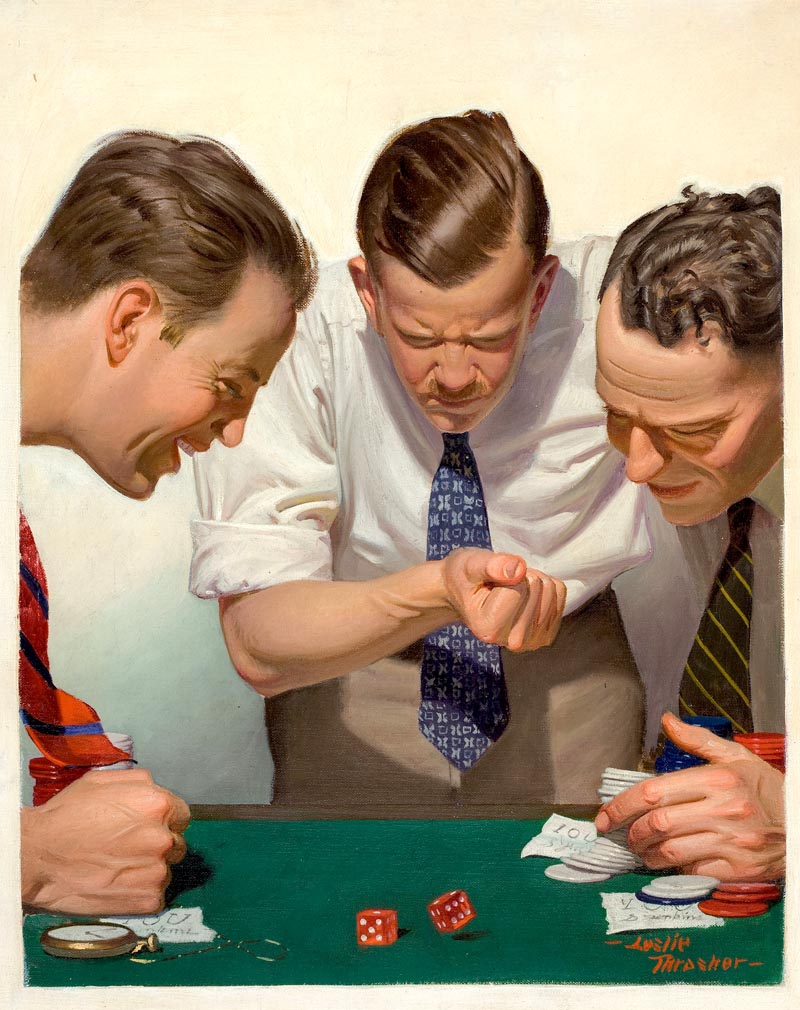

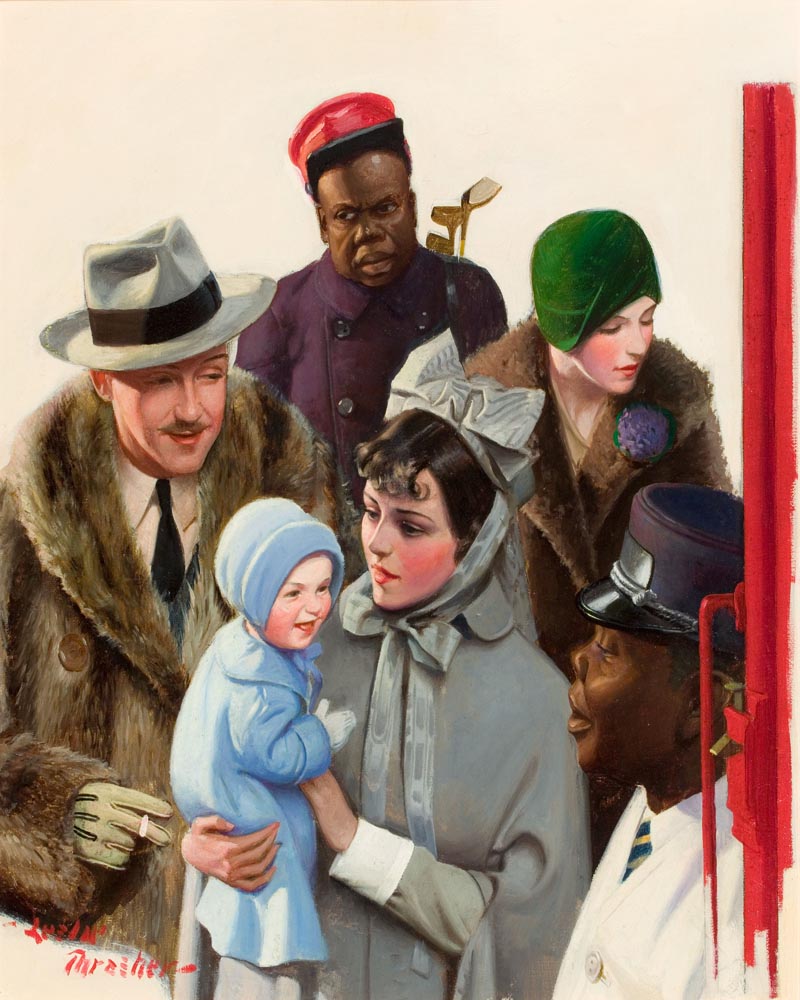

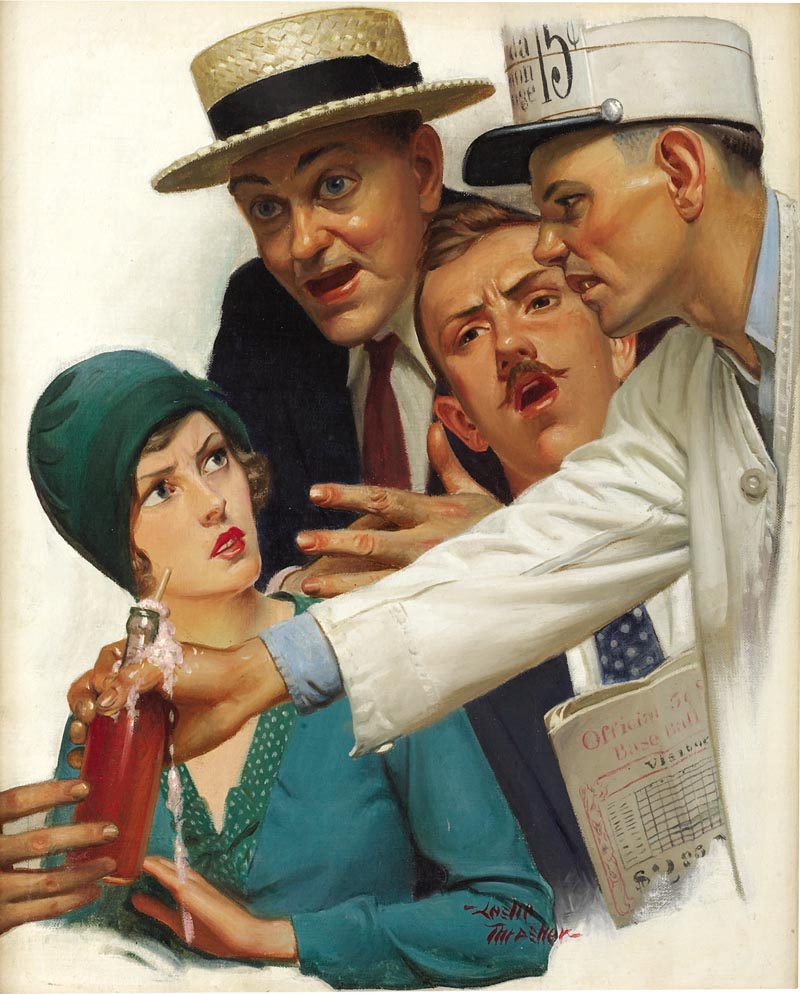

Liberty magazine's publisher may have failed to sway Norman Rockwell's loyalty to George Lorimer and the Saturday Evening Post... but the demon of temptation proved too powerful for another illustrator - Rockwell's friend, Leslie Thrasher. Rockwell writes that Thrasher "painted one of the most famous Post covers ever published. I still get letters from people who think I did it. It depicts a lady and a butcher standing on either side of a scale in which lay a chicken. The lady was pushing up on the scale; the butcher was pushing down. The cover appeared on 3 October, 1936."

"Some months later Thrasher came to my studio asking advice about an offer Liberty magazine had made to him. It was a five-year contract calling for Thrasher to do fifty covers a year at one thousand dollars a piece. "I can live on ten thousand dollars a year," said Thrasher, "so I can save forty thousand. At the end of five years I'll have two hundred thousand dollars. I'll be well off and secure for the rest of my life."

"I told him I didn't think he or anybody else could do fifty covers for even one year, let alone five. "Don't accept," I said. "You'll work yourself to death. And after the contract runs out, what'll you do? Nobody else will want your stuff." Well, he didn't know; maybe maybe it wouldn't be so bad; he thought he'd give it a try. And he went ahead and signed the contract."

"Liberty dreamed up a family around which Thrasher was to build his series (I forget the details; mother, father, children, and grandparents - something like that), and he set to work. One cover a week. He didn't last a year."

"After eight or nine months his house burned and he was so run-down and tired from overwork that he caught pneumonia and died."

"But the poor guy would never have lasted the full five years anyway. No man could have. Fifty covers a year? That's just too much."

"I still hesitate a bit between yes and no when somebody offers me a fat contract. Then I think of Leslie Thrasher and I can't say no quickly enough. security is very nice, but not if you have to kill yourself or your work to get it. Same with money."

* The text quoted today, the Norman Rockwell orange Crush ad, the photo of George Lorimer and the third Coles Phillips illustration are all from the book, "Norman Rockwell - My Adventures as an Illustrator" ©1979 Curtis Publishing Co.

* Thanks to Heritage Auctions for allowing me to use several of their scans of Leslie Thrasher originals in today's post.

* The scans of Thrasher's Post cover was found at mymags.com

0 comments:

Post a Comment