Chicago, as the advertising capital of the world before Madison Avenue in New York took over, meant that illustrators in that city were bound to find work doing commercial art. As we saw yesterday, Walter Haskell Hinton got his start doing just that, but he knew that he shouldn’t limit himself to advertising if he wanted to build serious prestige as an illustrator. He explained,

"In fine art they look down upon commercial art of course, but even the illustrators that illustrate new covers for magazines, they look down on the fellow that’s advertising somebody’s toothpaste."

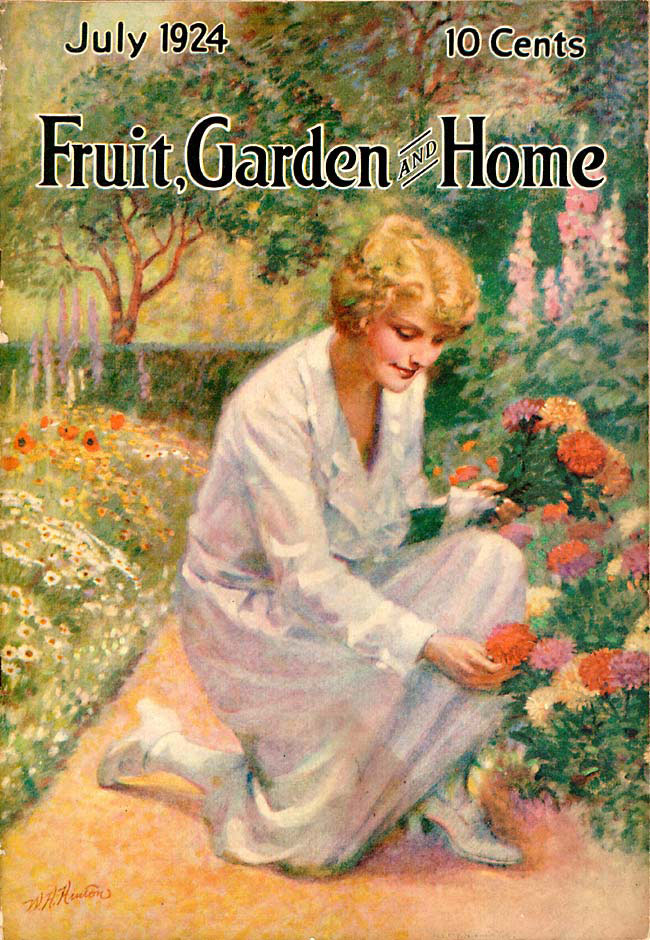

Hinton first established his reputation as a cover artist in the area of agricultural magazines. Although they served to advertise the magazine on the news-stand, Hinton’s farm scenes often looked more like fine art paintings than advertising illustrations. Radio had not yet penetrated all rural areas, and so magazines and newspapers were the main source of information for farm families. It was not unusual for people of even modest means to have around four subscriptions, and covers were used to decorate or for crafts.

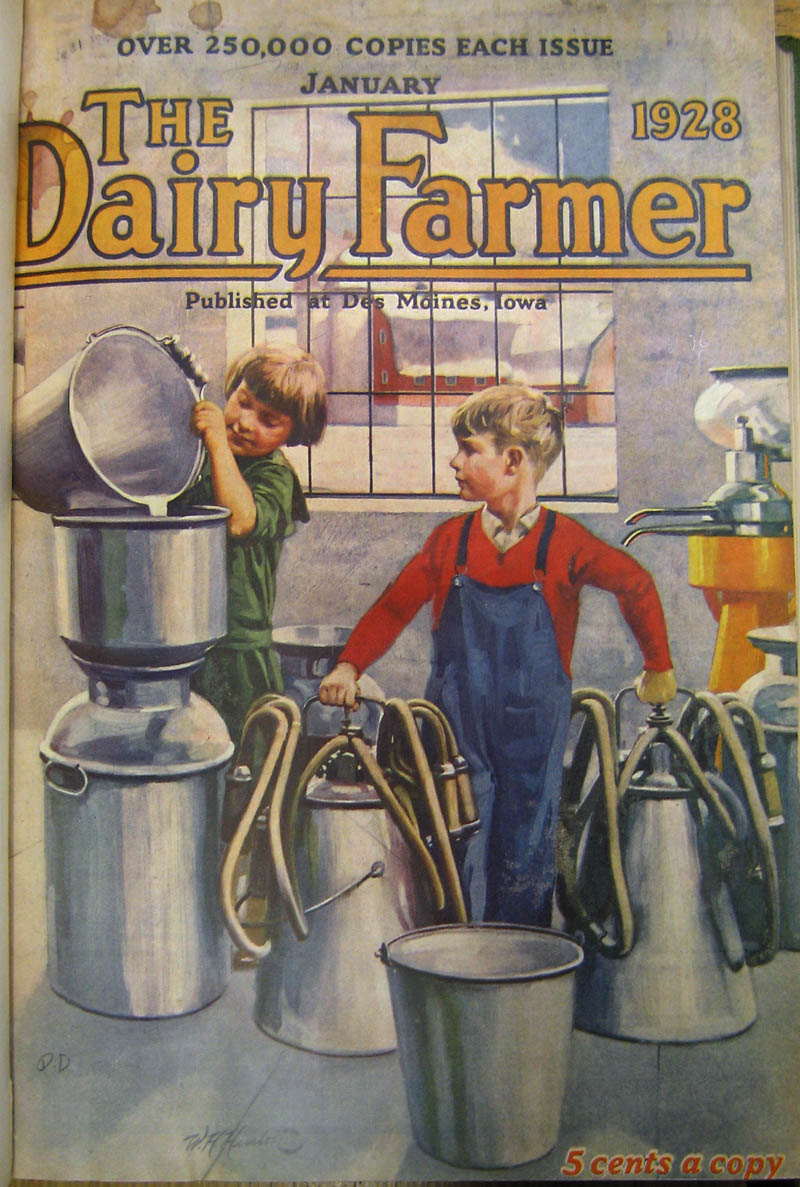

The mid-West was a farming region as much as a manufacturing one, and so Hinton had ready examples nearby to help the realism of his farm pictures. Here, children help with chores using modern dairy technology; agricultural magazines promoted modernism on the farm just as much as more mainstream periodicals like Ladies Home Journal promoted it in urban centers. Hinton was so effective at capturing the transition to new lifestyles from old that John Deere staff remarked he was obviously an expert on farm life – but Hinton had never lived outside of a city!

Hinton had, however, been camping, hunting and fishing since childhood, since most Victorian middle-class boys were encouraged to pursue spiritual and manly experience in the wilderness. His early training as a landscape painter under Albert Fleury also gave him the skills to depict any sort of outdoor environment.

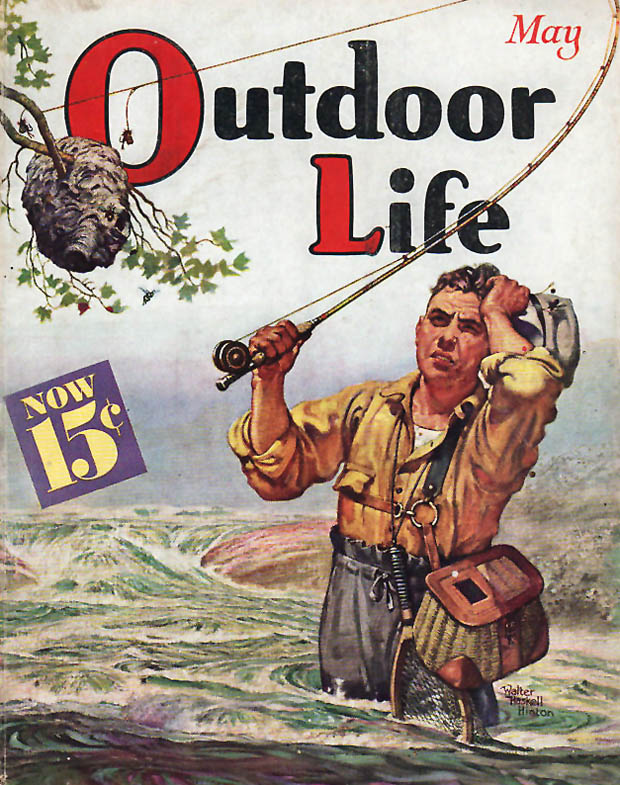

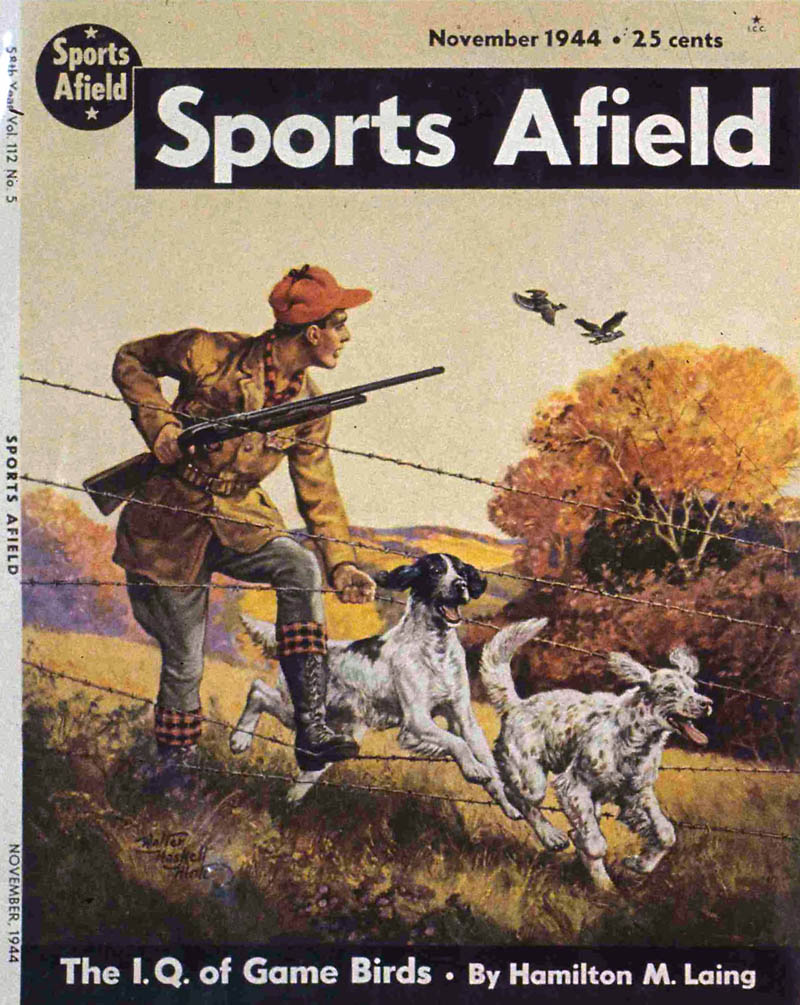

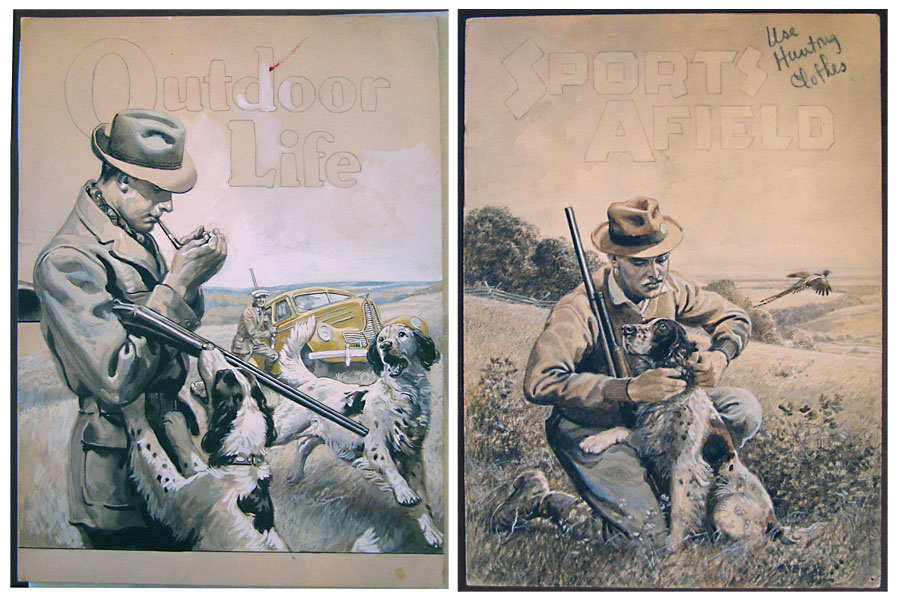

Naturally, when the Depression hit and he had to turn to freelancing, he solicited work from hunting and fishing magazines like Sports Afield and Outdoor Life. The latter eventually objected to Hinton working for both publications at the same time – it was not accepted practice for competitors to use the same artist, once that artist had become a regular contributor. They actually offered to pay him his original fee PLUS what Sports Afield paid in order to keep him. It seems Hinton turned this offer down; there are more Sports Afield covers overall and they appear for longer.

Hinton was an avid fisherman and loved dogs, so the majority of his covers show funny and serious scenes of fishing and dogs, and of fish on the line. In these, there is a touch of Norman Rockwell’s country characters and predicaments. As for Hinton’s hunting scenes, they do not often show the hunter actually taking a shot. Instead, the game is generally getting away in the foreground. This probably reflected Hinton’s distaste for killing animals:

"I felt like a dirty criminal. You just pull a trigger and you take something that you couldn’t replace if you lived to be a thousand years. That’s their home and they enjoy their lives and have just as much a right to live as I have. But I was brought up to hunt and fish. Of course, fish I don’t feel so bad about because they are a bunch of cannibals anyway. But as far as killing animals, I even feed them out here at night."

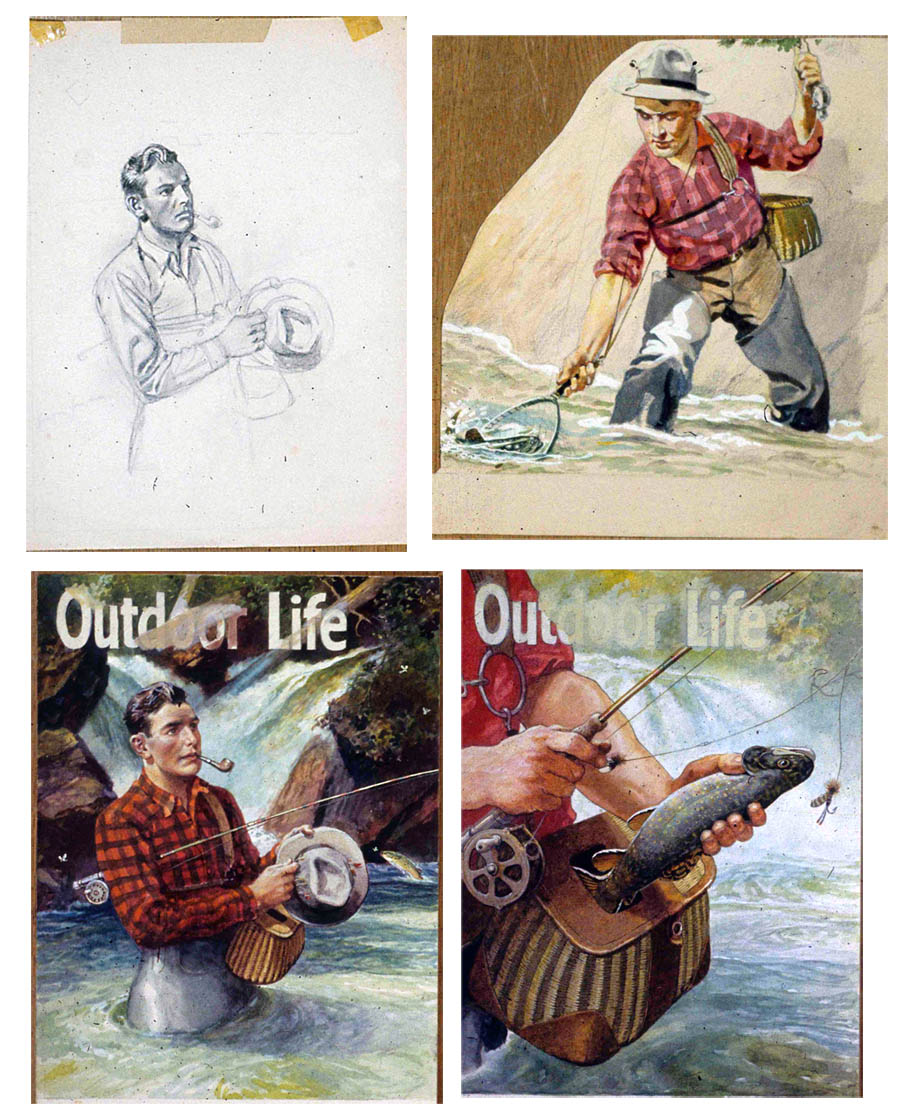

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Hinton had been trained to work out of his memory or from life. He sometimes used photographs for reference, but he thought copying photos outright to be quite abhorrent. He made studies of figures and animals, frequently out of his head, and sometimes used his son or himself as models. The redshirted fisherman below is his son.

After brainstorming many thumbnails, he worked up a comprehensive sketch to submit to art directors. These were occasionally rendered in full color, but more often he only used a limited palette in gouache. The final paintings were mostly done in oils on canvasboard, around 16x20” large.

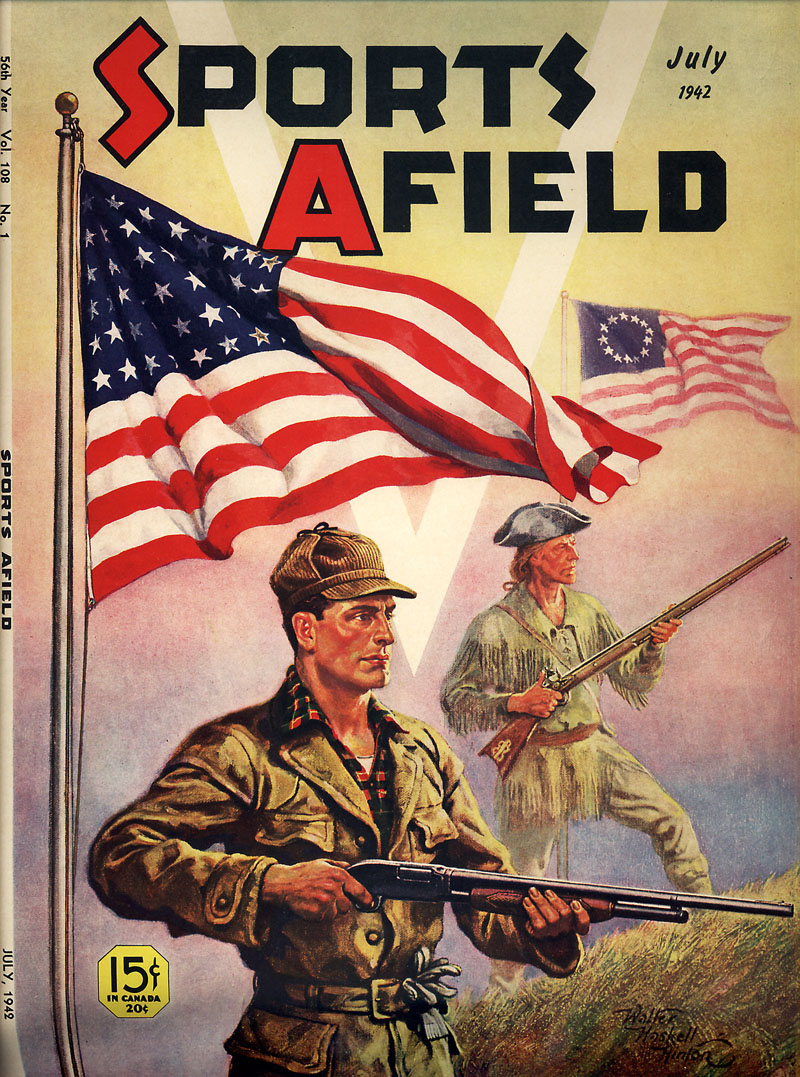

During World War II, Hinton made several patriotic covers depicting soldiers. For the July 1942 issue of Sports Afield, he juxtaposed a hunter with an 18th century War of Independence fighter in buckskins. A V for Victory floats in the background. The suggestion was that hunters’ marksmanship was an important skill for national defense, that the right to bear arms continued to be an essential part of nationalism. Hinton was very patriotic himself, and extremely proud of his son, who was a pilot with the US Army Air Corps during the War.

The inclusion of the buckskinned man related to Hinton’s other body of work on Western history, that he was producing at the same time for the pulps and calendar companies. We will look at those tomorrow.

An original painting for Sports Afield, not shown here, will be on display at the Downtown Gallery in Knoxville Tennessee throughout December 2010 and early January, 2011, along with numerous other works by Hinton.

* Jaleen Grove's critical biography of Walter Haskell Hinton, published by the Ewing Gallery at the University of Tennessee, began as a fairly brief exhibition catalog essay. It grew into a 96-page book when a wealth of interviews and primary documents were obtained. The book differs from this series on Today’s Inspiration in that it explores key issues in the cultural production of commercial art, both the troubling aspects of mass-culture images and the material pleasures of them.

Because it is a non-profit educational endeavour for which she volunteered her time, Jaleen would like to invite you to advance-order a copy or donate to the project, to help with production and distribution costs.

* Walter Haskell Hinton official website

0 comments:

Post a Comment