Extremely little has been written about calendar art, probably because it has been considered the exact opposite of everything thought to be artistically tasteful by modern artists and art critics of the 20th century. Furthermore, its fan base has been mostly quiet and apparently not as self-advocating as collectors of other once-derided art forms, such as comic books and science fiction art. That calendar art has remained undocumented for so long is surprising given how ubiquitous it has been. According to the 1953 annual report of manufacturer Brown & Bigelow, 93% of American houses had calendars in them, and 47% of housewives shopped for them even though most received calendars for free from advertisers.

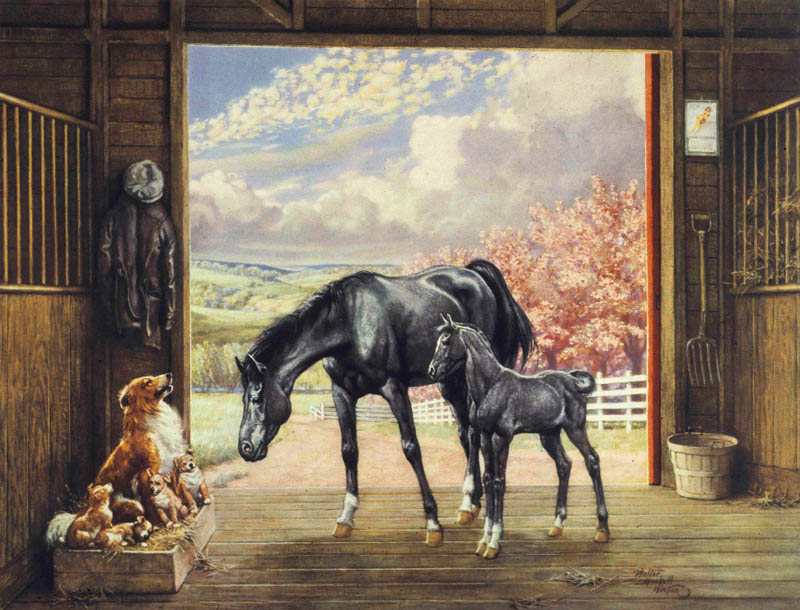

Calendars used to be issued with only one image printed on cardboard with a pad of the months stapled below it, which were torn off as time went by. In this barn Walter Haskell Hinton has placed just such a calendar, featuring a pin-up girl, on the wall to the right.

The space between the picture and the pad of months was printed with the name of an advertiser. Brown & Bigelow reasoned that, “Since housewives spend an average of 4 hours a day in their kitchens, the constant repetition of an advertiser’s sales message there will cause it to be virtually memorized.”

Calendars were a way for the advertiser to associate themselves with positive values, and those that were to be given away to a wide range of customers had to have pictures that were upbeat and inoffensive. Calendar art has often been dismissed for its clichés, such as the ennobled elk above, but such images were repeatedly issued because they satisfied tastes originating over 200 years ago that had never gone away, in which art was supposed to be beautiful and morally uplifting. Familiar subjects symbolically communicated traditional values: here, the majesty of Nature and nobility of the stag, an ancient symbol of virility. Selection and display of such an image affirmed the owner’s worldview and identity and conveyed this to others.

Hinton’s wildernesses are always idealized, with pristine forests and healthy animals. In his 1976 interview, he spoke of how a publisher once complained when he included a realistic dead tree, such as one find in any actual forest. An interesting circular situation emerges, where calendar publishers concluded the public wanted to see certain kinds of idealized images, and so kept on issuing them, which confirmed and strengthened that taste among the buying public, further constricting artists.

No wonder modern artists who valued experimentation hated the stuff! But for those who felt modernity was proceeding far too quickly, and who simply wanted their art to provide a break from life’s demands, traditional and perfected subjects were reassuring and inspirational.

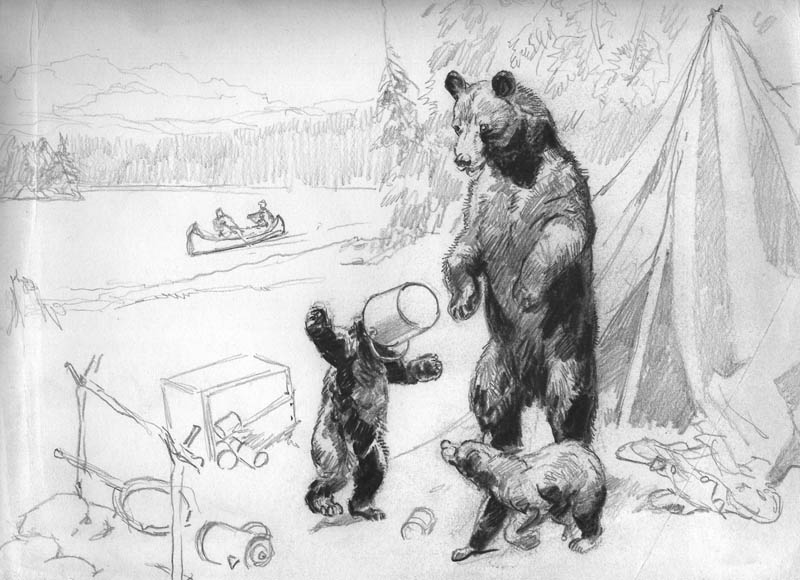

Yet even within this conservative business climate, there was room for innovation and self-expression. Hinton was an environmentalist before the term was coined, and portraying nature was for him a way of subtly critiquing the impact of modern human life. He frequently anthropomorphized his animals, bringing out human qualities in archetypical ways, as in the elk above, and in humorous ways, as in this sketch of a hapless bear cub with a bucket on its head. We might look beyond the cuteness to think about the impact of man’s encroachment on the wilderness, as the deer watching the fisherman seem to do.

Copyright © Brown & Bigelow

As the popularity of Westerns grew, Hinton found he could pursue this favorite theme of his in calendars too, in addition to the work he was already doing for pulps. Where the pulp magazine covers were almost exclusively macho, for the calendar art market he introduced women and romantic themes, such as in Starlight Trail above.

The calendar companies issued the images they bought from artists as large art prints as well. These were sold as “suitable for framing” to consumers and to hotel chain interior decorators. They were also distributed to jigsaw puzzle manufacturers, who produced millions of puzzles in the 1930s.

Image courtesy of the Ewing Gallery

Hinton secured important contracts producing calendar images for corporations such as John Deere, Austin-Western, and Washington National Insurance. His relationship with each lasted a minimum of 20 years.

Collection of the Ewing Gallery

Washington National appreciated Hinton for his knowledge of history. For them, he researched historically accurate scenes of George Washington’s private life suitable for kids, rather than the military exploits that other illustrators had proposed to paint. Washington appears spotlessly heroic and compassionate (when the above painting was completed, fox hunting was not yet controversial). The series was issued in packages distributed in elementary schools, an interesting confluence of corporate advertising, education, and inculcation of patriotic values indeed!

Hinton often included a dog in his work, be it magazine covers, advertisements, or calendar pictures. For heavy equipment manufacturer Austin-Western, a dog – rumoured to be the boss’s – sits next to the driver in every picture. This sentimental touch associated emotional warmth with the otherwise rather cold and imposing machines.

It is fitting to end this series with a painting Hinton kept all his life. This image of fox and pheasants was issued as a print, but unlike most of his work, he somehow retained the original art. In it, his earliest training as an academic landscape painter comes together with the traditions of sporting art and scientific illustration to present a dramatized scene of the struggle for survival between creatures.

Hinton’s greatest strength as an illustrator was his versatility. As I remarked in my first post about Hinton, he never specialized enough in any one area to win fame. But excellence in a specialization is only one way to value an artist. An illustrator such as Hinton, who had a lengthy career in a bullpen at an advertising agency, is better judged for how well they could shift gears according to clients’ needs. Hinton, who believed firmly that art should serve a greater purpose than just his own self-indulgence, made a point of developing every area of his potential so that he could be of service in as many situations as possible.

I would like to thank the Ewing Gallery and the Hinton family for inviting me to write on Walter Haskell Hinton and for providing access to images and documents.

* Many thanks to Jaleen Grove for this week's fascinating series on Walter Haskell Hinton! Jaleen's critical biography of the artist, published by the Ewing Gallery at the University of Tennessee, began as a fairly brief exhibition catalog essay. It grew into a 96-page book when a wealth of interviews and primary documents were obtained. The book differs from this series on Today’s Inspiration in that it explores key issues in the cultural production of commercial art, both the troubling aspects of mass-culture images and the material pleasures of them.

Because it is a non-profit educational endeavour for which she volunteered her time, Jaleen would like to invite you to advance-order a copy or donate to the project, to help with production and distribution costs.

* Walter Haskell Hinton official website

0 comments:

Post a Comment