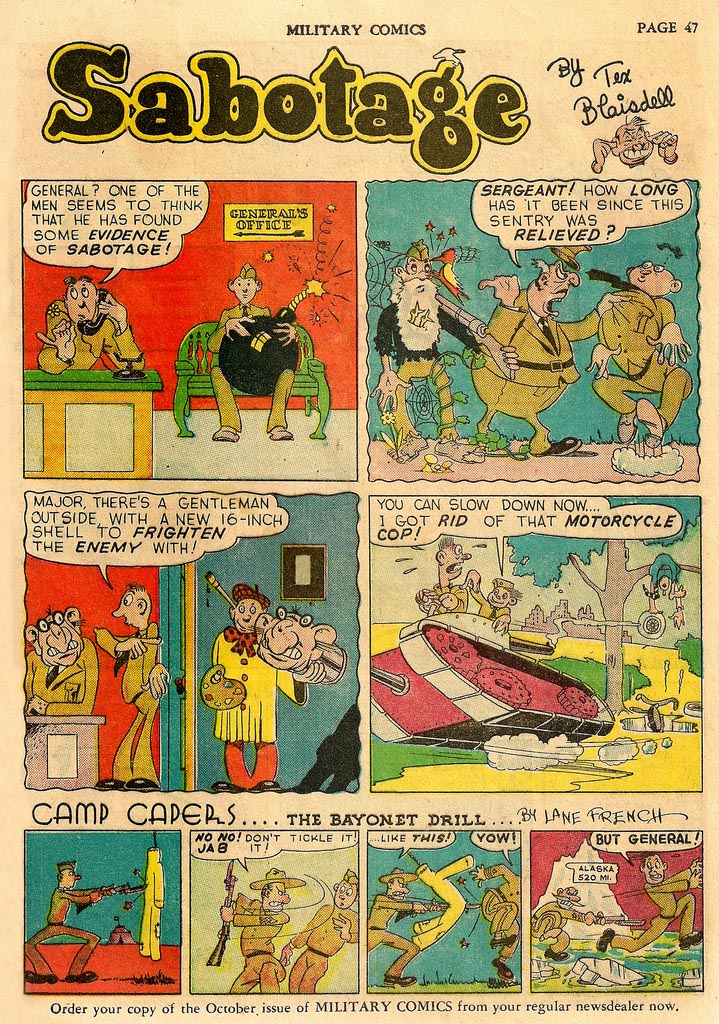

The Reubens, the annual awards ceremony of the National Cartoonists Society (of which I am a proud member) is just a few days away. As in previous years, I'm using this week as an opportunity to showcase some of the Luminaries of the NCS. Today, Tex Blaisdell.

The Reubens, the annual awards ceremony of the National Cartoonists Society (of which I am a proud member) is just a few days away. As in previous years, I'm using this week as an opportunity to showcase some of the Luminaries of the NCS. Today, Tex Blaisdell.

My friend Tom Sawyer (whose career was the subject of a week of posts here on TI in 2008) has graciously agreed to share another excerpt from his memoirs. In this section, Tom describes, as a newly-arrived-in Manhattan hopeful young kid, his first chance encounter with Tex Blaisdell.

Excerpted from Thomas B. Sawyer's memoirs:

Seated across from me that morning in the reception room at Avon Comics, where I was awaiting an audience with the editor, Sol Cohen, was another artist whose scuffed two-foot by three-foot zippered, suitcase-handled leather portfolio identified him as a professional. Lanky – skinny really – mid-30ish, with short, thinning curly reddish-blond hair and enormous ears projecting at right angles from too far back along each side of his head, his long-legged, skeletal frame didn’t come close to containment in the chair opposite me.

We nodded at each other.

“You new in town?”

Not a difficult deduction: my samples were in a large manila envelope (I had already priced portfolios like his, and resolved to purchase such a badge with the proceeds from my first assignment).

“Yeah.”

“Can I see your stuff?”

He examined my work briefly, without any discernible reaction, then handed it back. “You be interested in picking up some background work?”

Unfamiliar with the term, but reluctant to seem too green, I guardedly faked it: “Yeah. I might.”

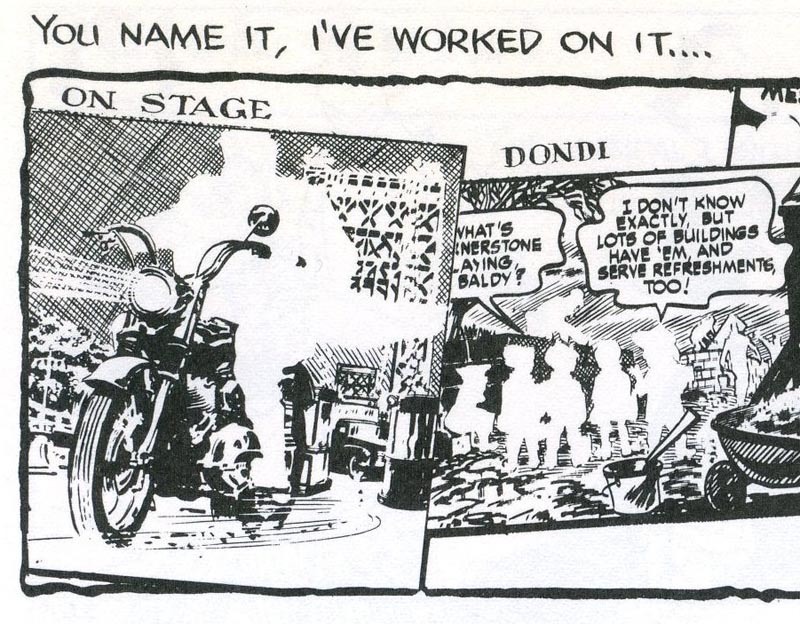

While he explained that he had been assisting a very busy artist, Leonard Starr, who could use more help, it registered for me that the term ‘background’ almost had to mean just that: buildings, cars, furnishings – while this Starr fellow, whoever he was, drew the figures.

He jotted something on a scrap of paper, passed it to me: “I’m Tex Blaisdell. C’mon by the studio…” Just then, the inner door was opened, and he was beckoned inside. I read the note he’d given me.

144 West 57th Street – 4th floor – rear.

Newcomer that I was, I may have been the only person in the vicinity who didn’t know that Leonard Starr was one of the most prolific and gifted people working in a business where, at that time, except to aficionados, artists were largely anonymous, rarely signing their work.

Though I’m not sure why it was so, it’s worth mentioning here that then, and continuing throughout my life it did not ever occur to me to seek a steady, salaried job, so ‘picking up some work’ was just what I wanted. And while I hadn’t considered the possibility of serving as anyone’s assistant, I figured hey, why not? None of it was forever.

My meeting that morning with Avon Comics’ editor, Sol Cohen, was encouraging, with his promise of an assignment within the next few weeks. Sol, incidentally, was a pleasant, Groucho-moustached guy, late 30ish, a WWII veteran whose most notable characteristic was the consistency of his costume. Every time I met with him, summer or winter, he wore the same increasingly tattered, moth-eaten olive drab GI sweater.

A few mornings later, I showed up at the smoke-filled studio on West 57th Street, where Tex greeted me and introduced his busy work-mates.

Artist Carl Anderson, about my age, nodded.

Ben Oda smiled, then returned his attention to the dialogue he was lettering. I was impressed to learn that he did the lettering for several major comic strips, including Terry and the Pirates.

The old man of the group, 40ish comic-book scriptwriter John Augustin continued punching the keys of his ancient portable typewriter, squinted briefly at me through smoke from the cigarette clamped between his lips: “Yo.”

Tex jerked a thumb at an unoccupied drawing table, where I deposited myself, not really knowing what to expect.

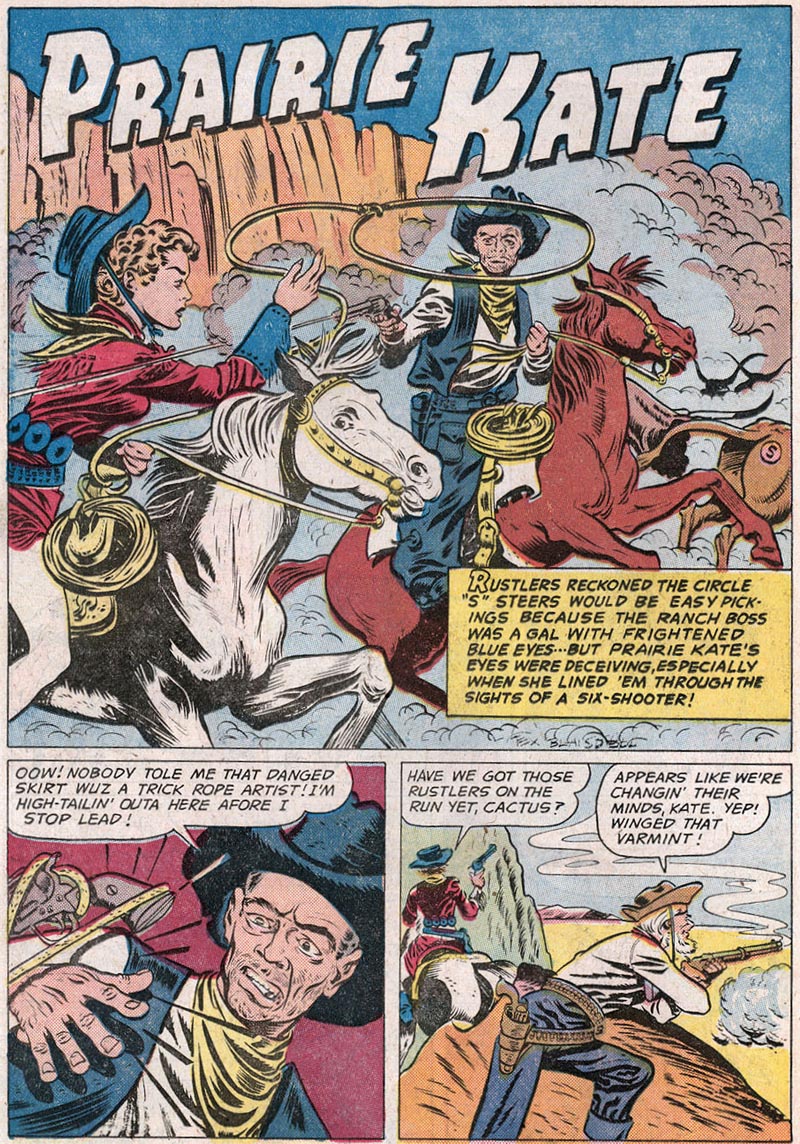

I found out in a hurry when he shoved several half-sheets of three-ply kid-finish Strathmore drawing paper in front of me, each one an original-art comic-book page containing six or seven panels of already-inked borders and dialogue, and my first viewing of Leonard Starr’s dazzlingly penciled-and-inked realistic figures. To my astonishment they were as well-drawn as those of the master, Milton Caniff. The remaining space in each panel was either blank or bore sketchily penciled indications of interior or exterior objects. The story Starr had illustrated was a Western, and one of his figures in particular, a kneeling gunslinger, really wowed me. “He works from photographs, right?” “Nope…” Tex waved at the tools on the adjacent tabouret – India ink, pencils, pens and erasers – and at the nearby filing cabinet. “Scrap – just about anything you’ll need…” ‘Scrap,’ a term I hadn’t learned in art school, meant reference photos and magazine clippings of everything from automobiles to guns, railroad trains, trees and so on. “…Seven bucks a page. The deal is – unless it’s in the figure’s hand – youknow – like a gun, it’s background. You draw it. Go ahead. Start.”

And, within a few minutes I was working around Leonard’s figures, penciling, then inking lamps, furniture, crockery or whatever else was needed to fill up the empty space, to add atmosphere and otherwise help tell the story. And in those frames containing no humans or animals, I drew appropriate scenery, from foliage to rock-formations to town-scapes. The latter, with dialogue balloons coming out of windows, I quickly learned, were jokingly described as ‘talking buildings.’

As I took in my surroundings, I knew that if I’d had any doubts that I was in The Real New York, this particular Alternate World would have instantly chased them off. The studio’s two relatively bare main rooms seemed to my eyes fully furnished, containing as they did four or five drawing tables, chairs, and Augustin’s small typing desk.

And capping its specialness, the apartment looked out on, and was within earshot of the backside of Carnegie Hall and its rehearsal facilities. From there – morning till night, when windows were open – one could hear practicing: violinists, cellists, horn and woodwind players, both jazz and classical, plus opera singers, the whole shot. Also visible beyond the maze of ducts on the rooftop of the adjacent Little Carnegie Movie Theater were windows into several dance studios where ballet was being taught or rehearsed.

And – there I was, the kid from Chicago, alongside colorful, working artists and writers, laughing and telling jokes while earning my first few professional dollars. I’d been in the East for less than two weeks.

It would be a few days before I’d meet Leonard Starr, my eagerness to do so whetted by his remarkable talent – and by Tex’s intriguing nickname for him: ‘Glamorous-and-Unpredictable.’

* As we close this excerpt from Tom's memoirs, I'd like to add the following from our most recent correspondence. Tom wrote:

"Tex (real name: Philip) had no accent (unlike Johnny Prentice). He was just -- Tex (described physically in the excerpt). And when I hired Tex, it was for backgrounds on my remaining comic-book work, which I was phasing out of, and for my increasing business from Johnstone & Cushing. Actually, I didn't have an outside studio by then -- I was going in to J&C in Manhattan several days per week, and the rest of it was done at my apartment in Jackson Heights, which was where we were working we received the call about Stan and Alex. I asked Tex because he had continued to work in that capacity for Leonard (and others, I believe). He may have picked up a few jobs from me and done them elsewhere -- and that working relationship only lasted a few months, after which I'd stopped doing comic books, and simply went in to my workspace at J&C every day."

Tom added, "To my knowledge, Tex never worked for J&C. He did bigfoot comic book work on his own, though I don't recall any specifics. Tex was very bright, very witty, well-read and unselfconsciously hip, like most of our crowd, a natural intellectual, an autodidact who never graduated from college. Tex and his beautiful wife, Lainie, lived in Whitestone, Queens, with their two handsome and very nice kids, Bruce and Barbara."

From my own research in the last few days I can add a couple of noteworthy accomplishments to Tex Blaisdell's story: He was the artist on the Little Orphan Annie newspaper comic strip for several years - from 1968 until 1973.

And in that capacity, Tex Blaisdell made a celebrity appearance on an old game show called "To Tell the Truth" (I used to love that show when I was a kid). See if you can guess who is the REAL Tex Blaisdell (well, the self portrait in his bio above kinda gives it away)...

* Many thanks to Tom Sawyer for sharing this wonderful excerpt from his memoirs with us.

The text of today's post is Copyright © 2010 by Tom Sawyer Productions, Inc.

* I'd also like to thank Bruce Mason, my newest contact on Flickr, who not only shared his Tex Blaisdell comic page scans with me today, he took the time and effort to locate additional scans online for me. Many thanks Bruce! Be sure to check out Bruce's amazing Flickr photostream of vintage comic book page scans.

* Thanks also to Heritage Auctions for allowing me to use several scans from their archives to illustrate this post.

0 comments:

Post a Comment