Like many Brits growing up in the early 70s my first journey abroad was a holiday to Spain but my indelible memory of that trip was of seeing armed guards patrolling the streets carrying machine guns. From 1939 until his death in 1975 Spain was ruled by the rightwing regime of General Francisco Franco and the country did not experience democracy until 1978. For the artists of Sellecciones Illustrada, growing up in Barcelona they would have experienced a society where dissent and free speech were crushed, where concentration camps and forced labour were common punishments and where even their own language of Catalan was suppressed. In this environment free thinkers and dissidents were naturally attracted to the left, something that was highly dangerous under Franco’s stridently anti-communist regime.

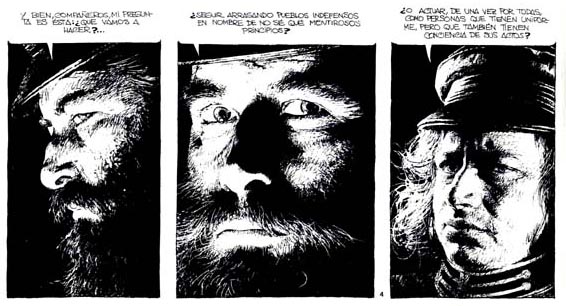

One of Luis’ first introductions to leftist politics came in 1964 from his fellow studio member Florenci Clave. At that time Clave was one of the most prolific romance artists, drawing primarily for Valentine, but he was also a member of the clandestine PCML group – The Marxist Leninist Communist Party. Clave organised some of the artists together to publish the experimental magazine Altamira and one night arranged for a showing of Sergei Eisensteins’ banned Soviet masterpiece Battleship Potemkin... After the film had finished he tried to encourage the group to discuss the movie but one by one they drifted away, fearful of being associated with anything so politically inflammatory.

Soon after, Clave’s British strips mysteriously dried up and it later emerged that under torture one of his colleagues in the PCML had given his name to the Policia Armada and the artist had been forced to flee to Paris. Like Luis, Clave found work in Paris with Pilote magazine but in the '70s he returned to Spain and met up with Luis in the apartment of his friend (and by that time fellow comic book artist) Marika. As Luis remembers; “Clavé put a pistol on the table in Marika's apartment, and said: "It is time for armed struggle, we must act against revisionism and capitalism. Do You want to be activists in the Marxist Leninist Communist Party?”

Perhaps not surprisingly the pair declined.

Following the artistic breakthrough of Chicharras much of Luis work in the '70s concerned itself with issues that were either personal to him or political, often taking up the causes of suppressed minorities such as the American Indians. As with Chicharras he would draw strips as the mood took him and then find a venue for them later, placing them in titles such as Scop, Bang, Pif, Eyez, Pilote and the highly politicized leftist magazine Trocha ( later renamed Troya) for which he was one of the founders.

(Below: "Tecumtha" from the first issue of Trocha magazine)

“Our intention in creating Trocha during the Spanish political transition was to help the country move away from the ideology of the dictator Francisco Franco. The group of professionals who founded Trocha were all left-wing with many sharing a Marxist /Leninist /Maoist ideology . We thought it was the solution for the poorest of the land, equal rights and duties for all people. Soon I discovered that in communist countries the conduct of political power was similar to the behavior of Nazi political power."

"The two ideologies (radical Communism and Nazism) even shared a similar popular iconography: the fabled leader, great and powerful directing the "broad masses."

"Then came the political disenchantment in the majority of the members and sympathizers of leftist parties in Spain. Trocha’s circulation was about 20,000 and luckily we had no problems with censorship because we were in that Transition to Democracy. However one day my apartment was searched by the police when I was out. I know it had been them because when I made the complaint to the police in my district they said, no point in investigating because "we will not find any thieves." That was typical of the Spanish police system at that time, breaking into the homes of people on the left and pretending they had been robbed."

(Above: "Ley De Vida" from Pilote 61, based on a story by Jack London)

Following more work for Pilote and a lengthy recounting of the Algerian way of independence (co-drawn by Adolfo Usero) in 1980 Luis embarked on what was to become his masterpiece – the graphic novel "Nova2".

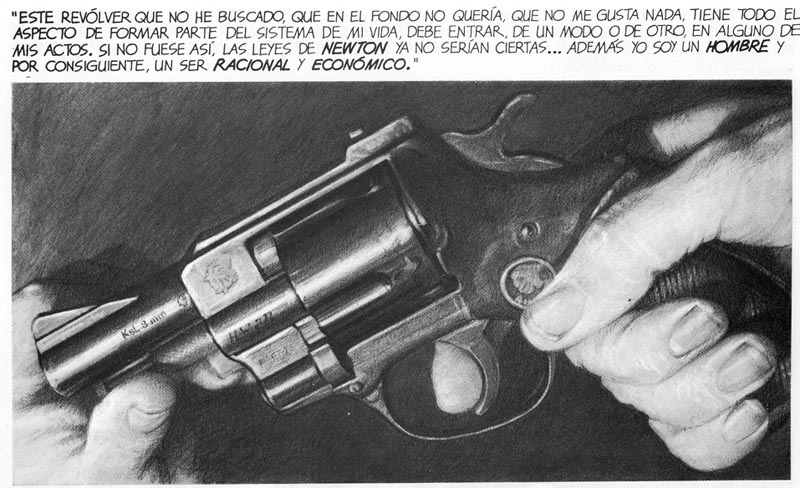

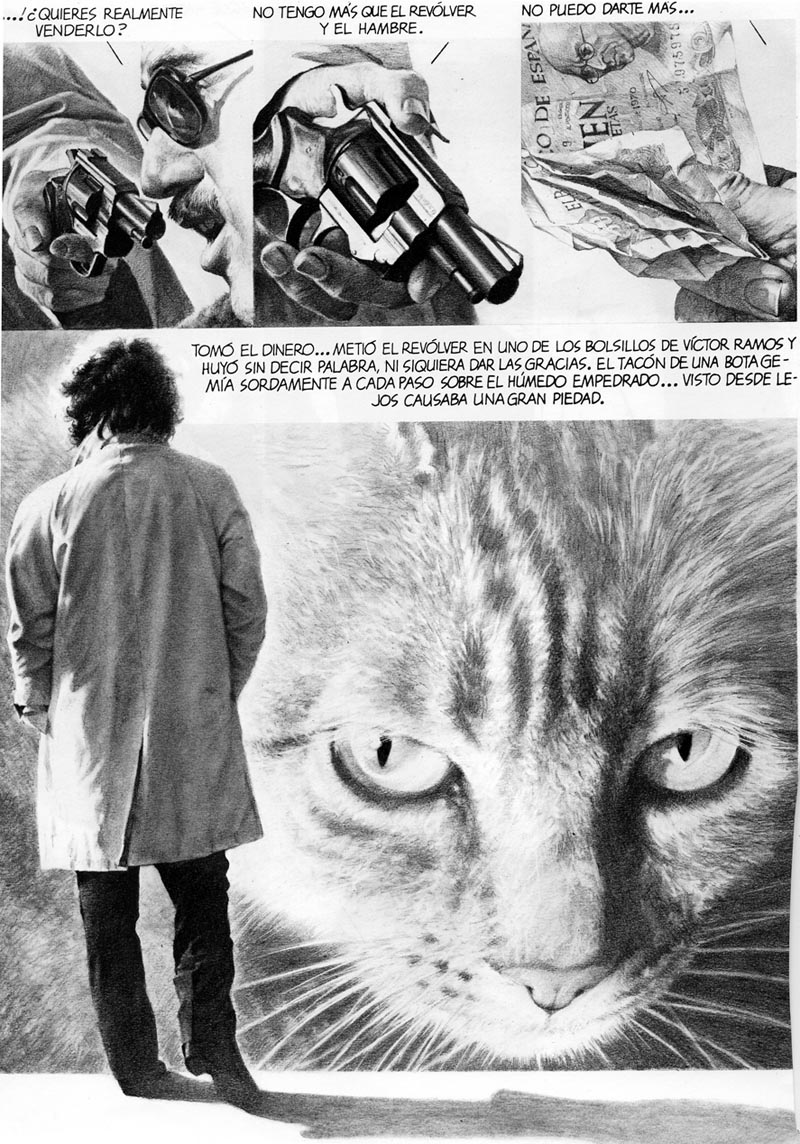

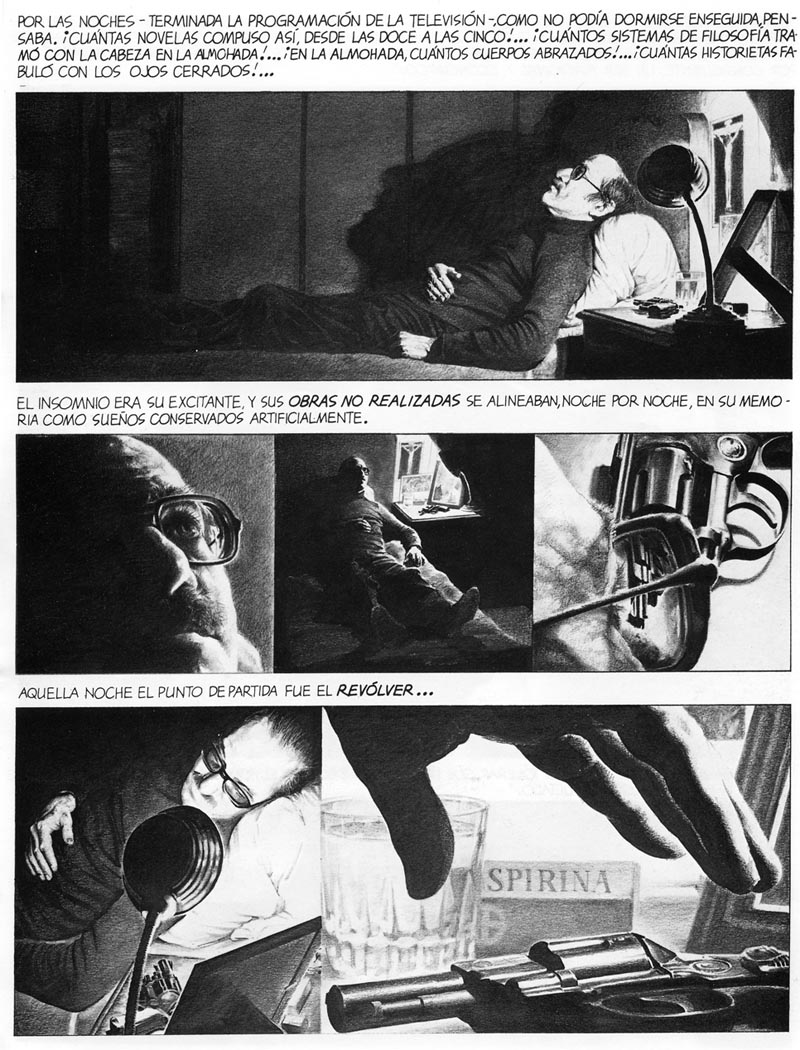

"Nova2" started life as a story set in the Sahara but as he was drawing the ninth page he heard the news that John Lennon had been shot and the project underwent a radical change of direction. The Sahara story abruptly stops and the first half of the strip becomes a meditation on hope and despair as a comic book artist buys a gun...

and then tries (unsuccessfully) to kill himself.

The second half tracks his life from the moment of conception through a childhood spent under the Spanish civil war and finally his fate at the hands of his pychoanalyst. Throughout there are references and quotes from the likes of Allen Ginsberg, Velazquez, The Beatles, Carl Jung and Alex Raymond. Visually it was a tour de force bringing together alll the various techniques and storytelling innovations he had developed over the previous 20 years.

After an opening section of detailed pen work the bulk of the book is rendered in rich, delicate swathes of graphite making it one of the most realistically drawn comics ever seen (and a pointer to a career change yet to come).

But throughout the piece Luis never stops experimenting and the ultra-realism is at times juxtaposed with expressionistic scrawls of pen and wash, With collages of Tarot cards, photo’s and even computer print-outs.

But even in a strip as revolutionary and complex as Nova2 (a story which could quite rightly be called the worlds’ first existential comic strip) there were meanings within meanings. The protagonist was a fictional comic book artist by the name of Victor Ramos, driven to despair at the futility of a life spent drawing British Romance comics. For the characters’ model Luis chose an old colleague from S.I. - also named Victor Ramos -who had himself spent many years drawing British romance comics, though we are assured that they are not one and the same. At one point we see the fictional Victor Ramos drawing a page of the romance story which is called “Love Strip” (the same title as one of Luis’ earlier Pilote strips), though this strip is a classic example of Luis’ British period.

To add to the confusion the person who sells “Victor” the gun is posed by Luis himself.

But beyond this there was a deeper, more personal and political element to Nova2...

As Luis explains: “There were two inspirations submerged in the script of Nova-2: Firstly the work of the Beat Generation, as well as the cultural phenomenon about which they wrote, specifically Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg (His poem "Howl" shocked me and changed my life because it generated the hippie movement in which I participated).On the other hand, returning to Barcelona from London, I joined the Marxist movement. The words of John Lennon; “The Dream Is Over" quoted in the book allude to my own experiences because the two movements for me, had failed. The character (based on myself) that sells the gun to “Victor” represents the end of my belief in the Marxist revolution, though these allusions may be difficult for the reader to understand."

In Nova2 the first half of the story describes the wanderings of a lonely, frustrated man guided by his subconscious In the second part we see the explanation of why Victor, my fiction, has that character. Victor was born the same day as Francisco Franco started the Spanish Civil War – a schizophrenic war that saw Spaniard pitted against Spaniard, even relatives on different sides facing each other.That's the explanation I built his character on – a schizophrenia diagnosed at the end of the story. The influence that the early years of childhood can have on later life was taken from an essay by Susan Sontag, who explained the importance of the mother in the formation of a child's psyche.”

The first half of Nova2 was sold to the Spanish magazine Totem and then on a trip to the U.S Luis managed to sell it to Heavy Metal where some of T.I.’s readers may remember seeing it. Later while talking with his fellow ex-Warren artist Jose Maria Bea the pair decided to create their own magazine which they named Rambla.

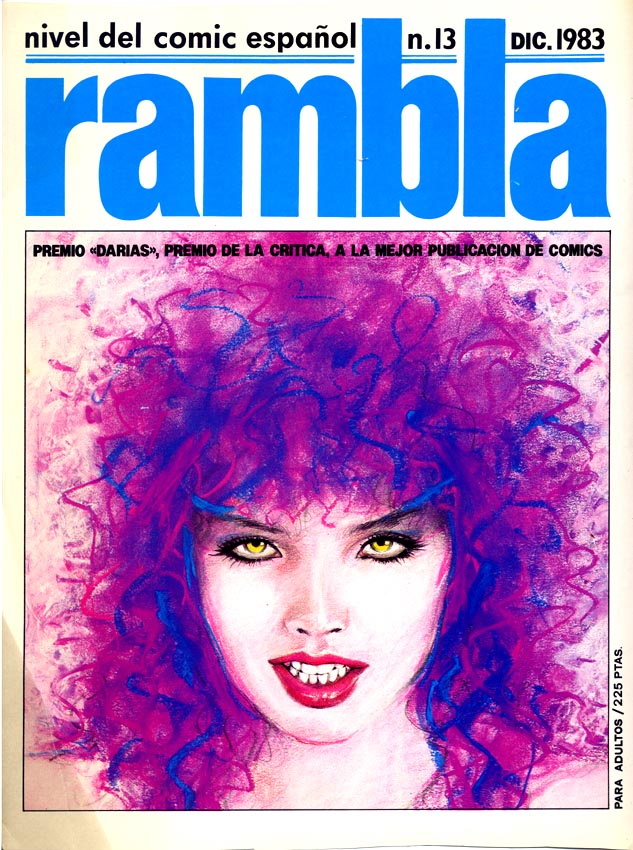

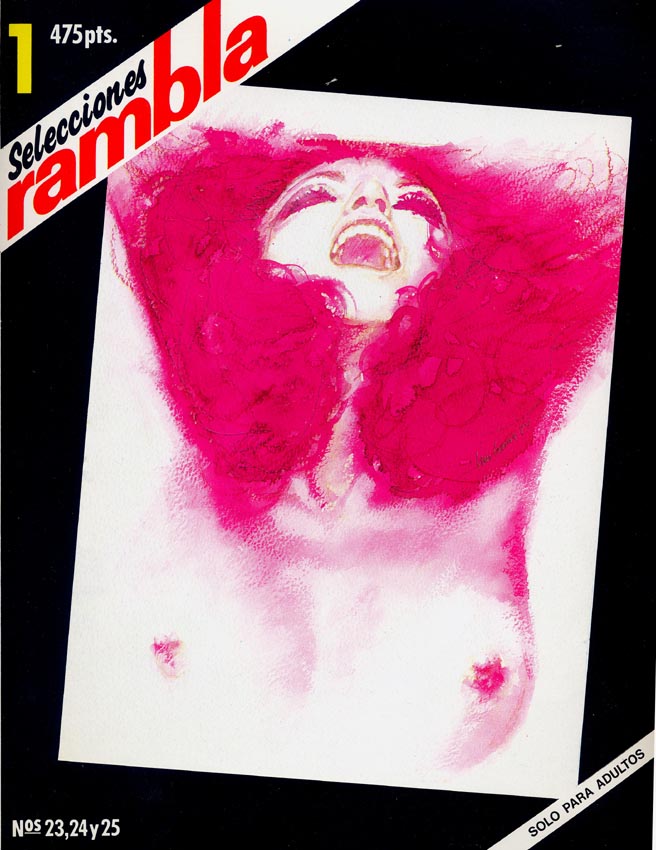

In the wake of Pilote and its’ successors Metal Hurlant, L’echo Des Savannes and Charlie Mensual other European countries created their own adult comic strip titles. In Spain this included Cimoc, Zona 84, Comix International and Creepy. Bea argued that if they could pool together the best Spanish talent from those magazines they would have a sure-fire hit on their hands and so with financial backing from Totems’ publishers Rambla was born.

The initial line up included contributions from co-editors Adolfo Usero, Carlos Gimenez, and Alfonso Font as well as Bea and Luis (contributing the second half of Nova2). While the others gradually faded away Luis and Bea ploughed on, growing from that single title to a mini-publishing empire that included the titles Rampa (for new talent), Rambla Rock and Rambla USA. Unlike the bulk of the adult-comics market Rambla was never restricted to a single genre such as Science Fiction or Horror but mixed autobiography with humour, historical and surreal strips and reprinted key earlier works by Luis, Alberto Breccia and Guido Crepax.

(Above: Rambla magazine, which featured numerous covers and illustrations from Luis as well as new and old strips)

From a contemporary viewpoint it seems like a remarkable achievement (which saw its editors working up to 14 hours a day just to get it out) but one which was tragically cut short by the economic meltdown which hit Spain the mid 80s. In six months the price of paper doubled and many publishers had to file for bankruptcy- including Rambla- and soon almost the whole Spanish comics industry was wiped out.

When the industry you’ve spent your whole life working in suddenly disappears, what do you do?

We find out... tomorrow.

0 comments:

Post a Comment