Illustration buyers (primarily magazines and newspapers) came to understand the value of direct drawing and importance of “being there”. While an artist can work from a photo, or their imagination, it’s the sights, sounds, smell, and environment that help give an on-the-spot drawing a uniqueness all its own.

Illustrators became “visual journalists” to cover various topics around the world.

One art director, Leo Lionni became a driving force behind the “visual journalism” movement. He worked for Fortune Magazine from 1948-1960 and not only hired illustrators but also fine art painters. He encouraged artists “to do the things they weren’t accustomed too.” Illustrators were sent on assignments all over the globe to draw upon and interpret firsthand experiences.

Robert Weaver, a pioneer illustrator in the visual journalism movement, said: “Lionni trusted the artist, and once he picked the right practitioner, he left him alone.”

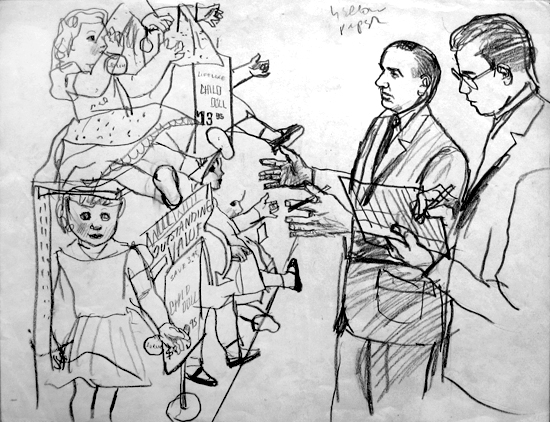

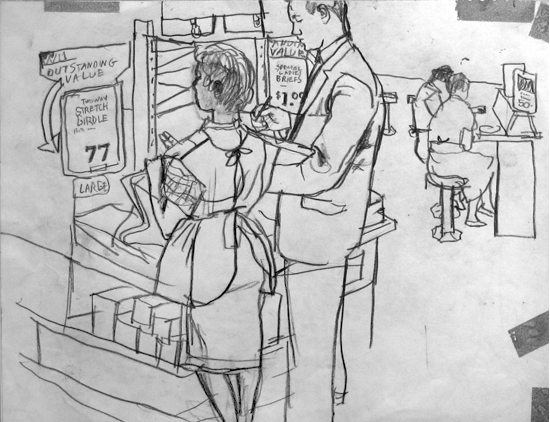

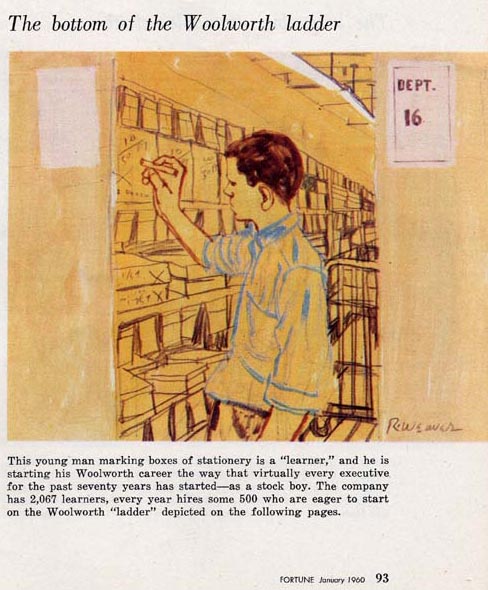

For the January 1960 issue of Fortune Magazine, Weaver was sent to Woolworth to illustrate an article titled “What´s Come Over Old Woolworth?”

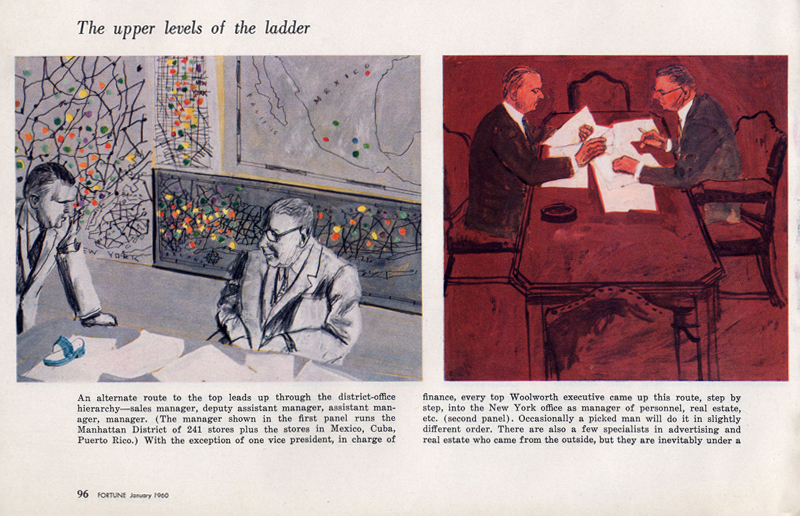

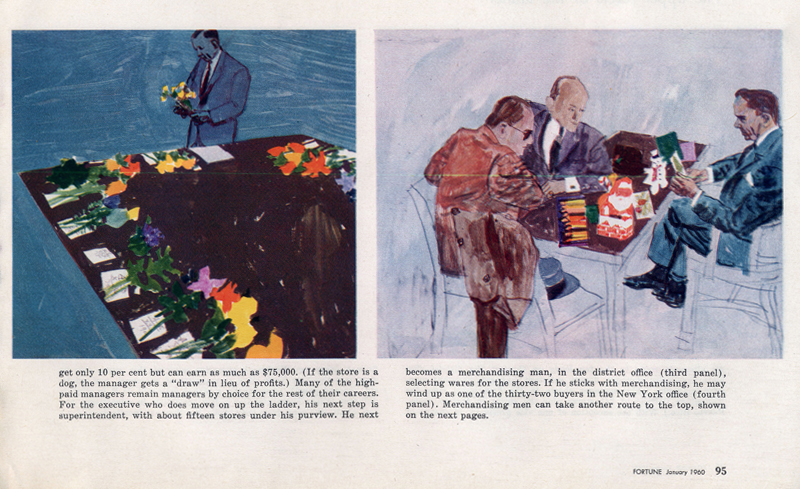

Weaver starts with a drawing of a stock boy and works his way up the corporate ladder.

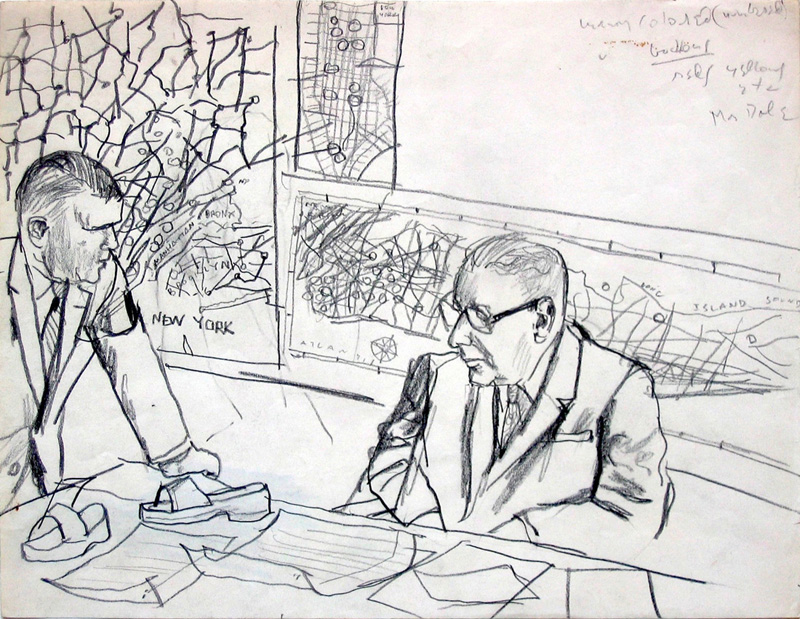

As he does this, the chairs and tables increase in size...

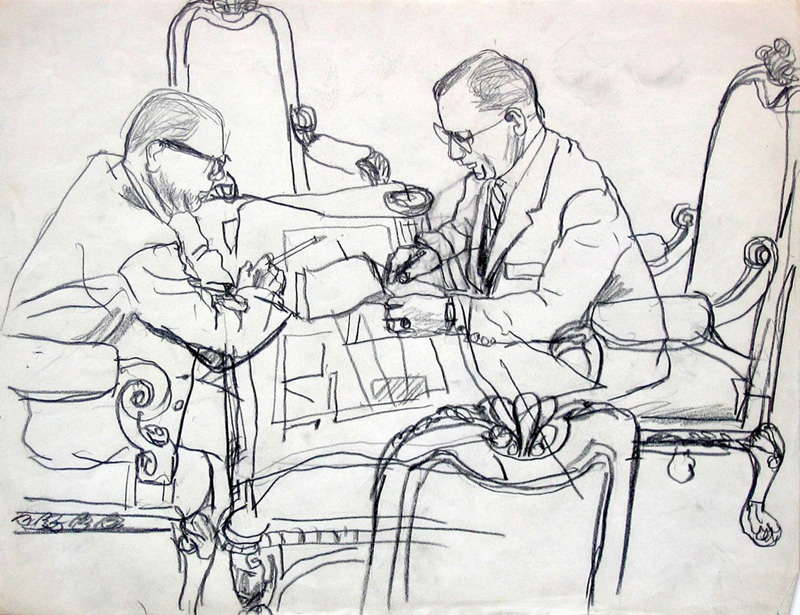

... to show the level of importance the men at the top were at that time.

Weaver described the process, “The drawings were rendered from life. I asked the stock boy just to stand for a few minutes...

... and finally, I rendered the big-time lawyers. As for process, essentially there is not a hell of a lot of transformations between the sketches and the finishes. I’ve simplified the finish a little bit and added some color.”

“I’ve actually made the pictures more decorative. My sketches are notes, and the color variations stay in the mind. I make the drawings without colors, and later I simply bathe the picture in what I remember to be proper light.”

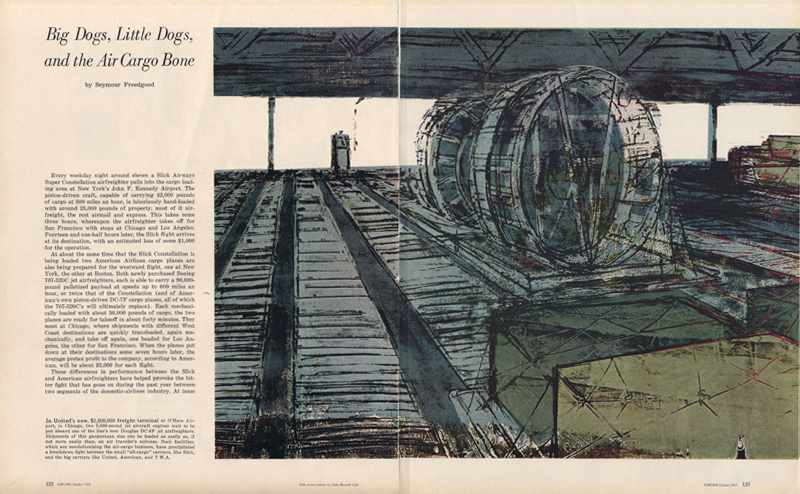

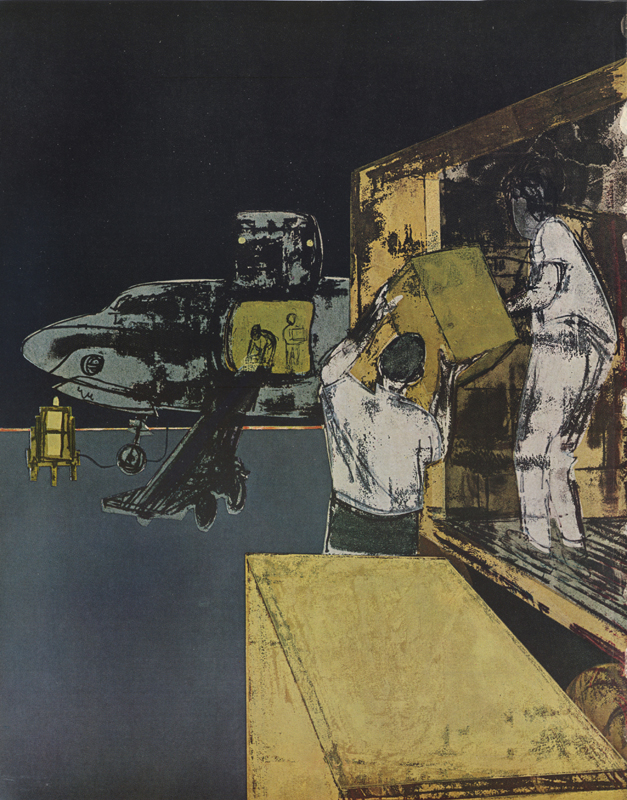

John Russell Clift, also for Lionni at Fortune, was assigned an article titled “Big Dogs, Little Dogs and the Air Cargo Bone”. As mentioned in the magazine pages: “Artist John Clift painted these pictures in the middle of the night, under the floodlights of O’Hare Airport. Nighttime is freight loading time at most airports.”

Also of note is that the credits don’t list them as illustrations. Instead they read “Silk-screen prints by John Russell Clift”.

Weaver added: “That was Fortune’s policy, to send artists on stories. I was sent to Ohio and Alabama, just all over. Sports Illustrated later did the same thing.”

Reportage was a widely accepted artform.

Continued tomorrow.

* Daniel Zalkus is an illustrator with a passion for on-the-spot drawing. You can see some of Daniel's own excellent work at his website.

0 comments:

Post a Comment