One; that the officer in charge of commissioning posters for the Office of War Information rejected Rockwell's proposal because he was "an illustrator" and the department had decided to use only fine artists, "real artists", for their poster assignments during WWII.

Two; that in the opinion of Saturday Evening Post editor Ben Hibbs, Norman Rockwell had created "great art" in the making of 'Freedom of Speech' and 'Freedom of Worship' - although Hibbs felt Rockwell would disagree because "he has always modelled himself an 'illustrator' with no pretensions of fine art."

The "pretensions of fine art"... "real artists"...

How the world perceives fine art vs. illustration and how artists perceive themselves in their capacity as visual communicators continues to frustrate and fascinate me.

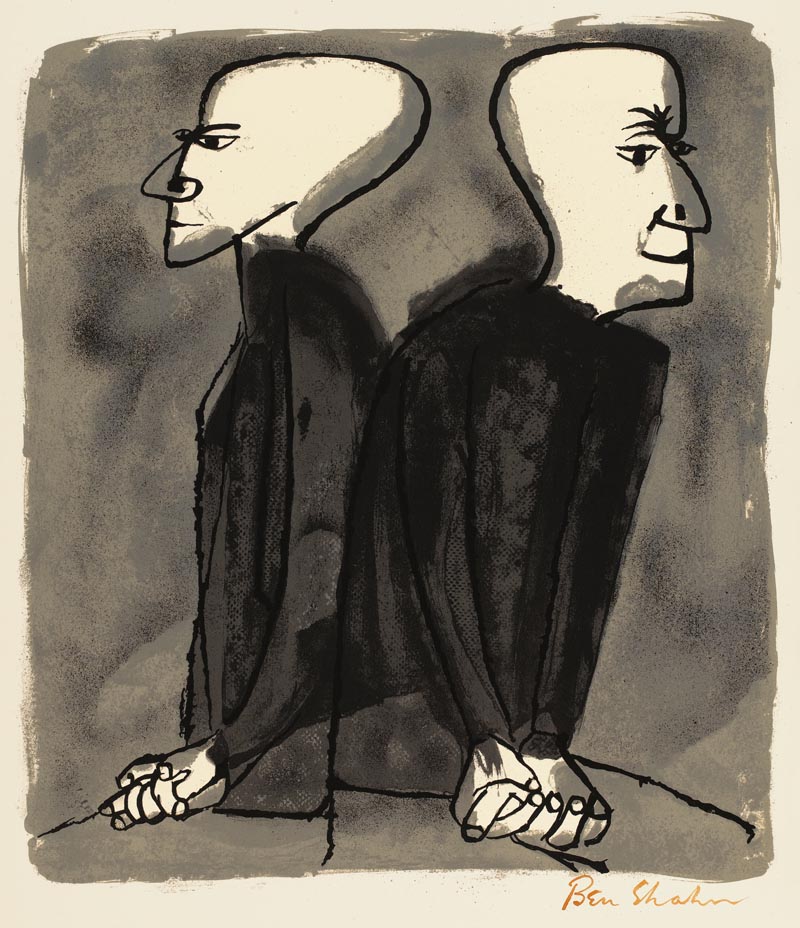

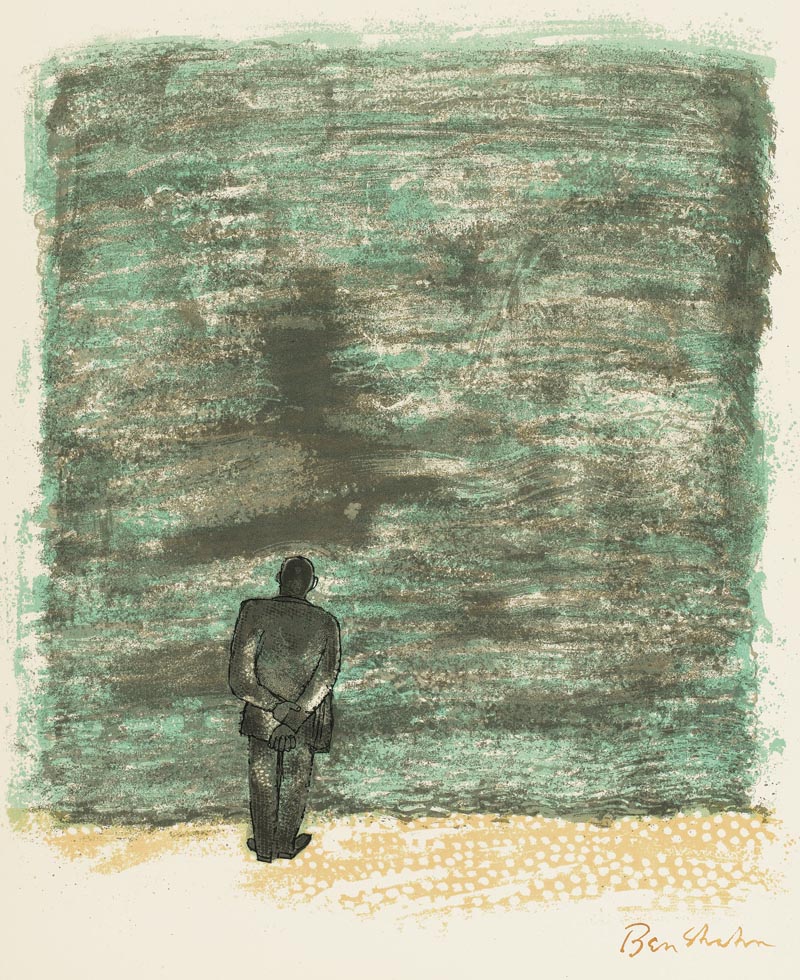

Based on the excellent, thought-provoking discussion that transpired on the last Ben Shahn post (and which I hope will continue on this one) many people, like the officer at the War Information department, have too narrow a definition of fine art and illustration and their relative merits.

It strikes me that most people don't 'get' what "real art" is or who "real artists" are. It strikes me that many people seem to have some pretty unrealistic expectations of both art and artists and the relative merit and quality of their work.

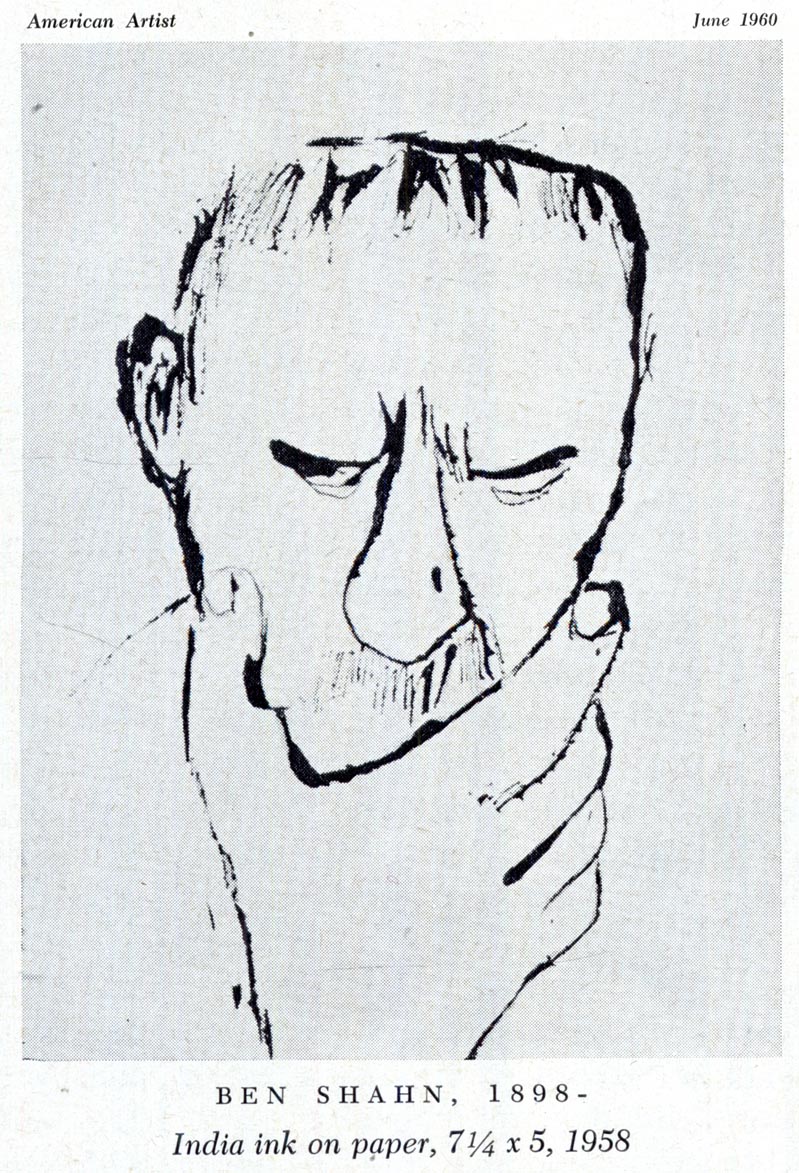

I remain unsure if Ben Shahn considered himself a fine artist or an illustrator - despite all I've read by and about him - or, quite frankly, if it would even have mattered to Shahn.

I do know that he considered himself a realist (no doubt Norman Rockwell considered himself one as well) and that realism was a 'trending topic' in both fine art and illustration during the mid-20th century.

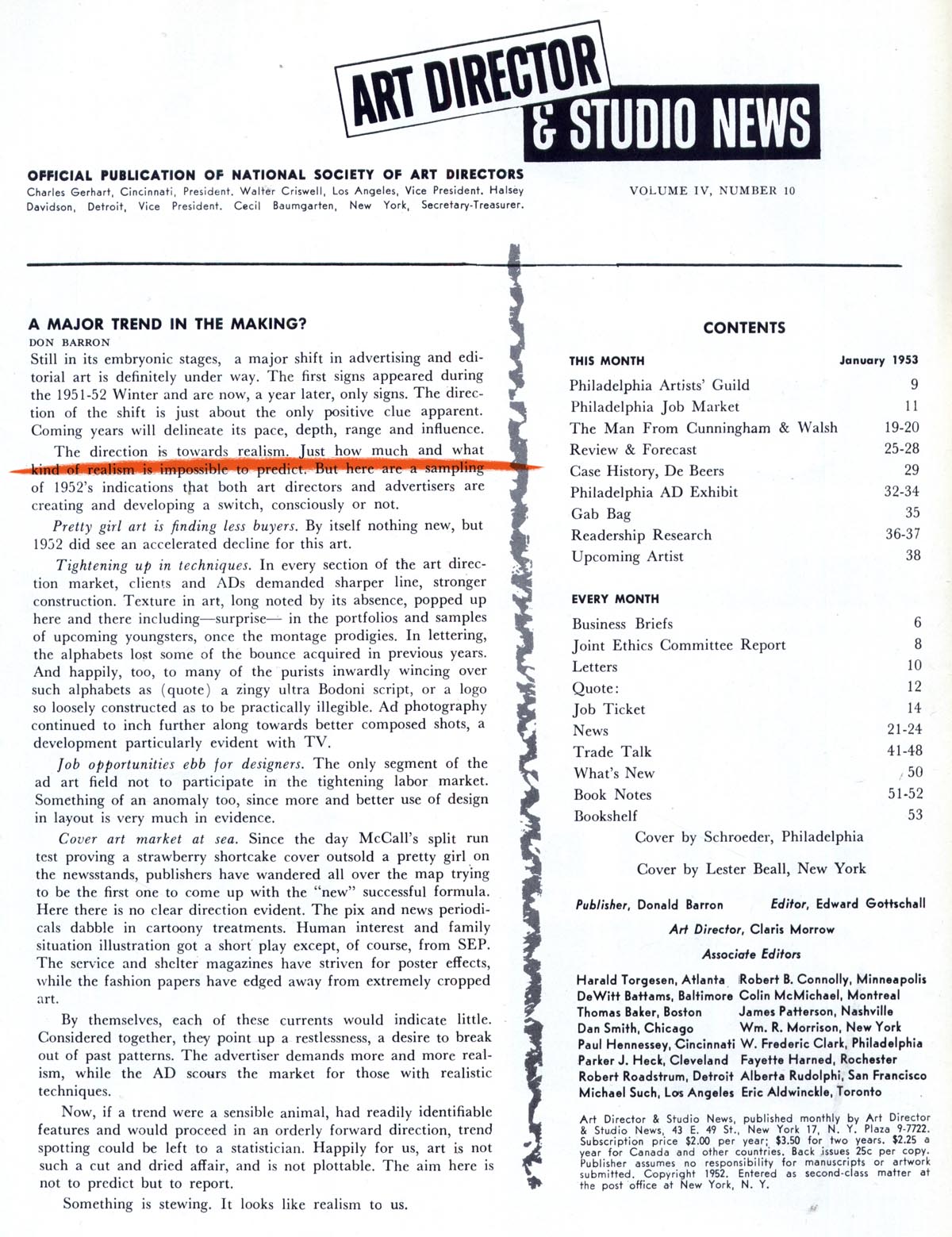

The January 1953 issue of Art Director & Studio News offered both an observation and a prediction about trends in commercial art at that time...

... a trend toward realism.

Further on in that same issue, a survey of industry professionals in major art markets across America confirmed the editors' opinions...

Illustration was becoming increasingly realistic.

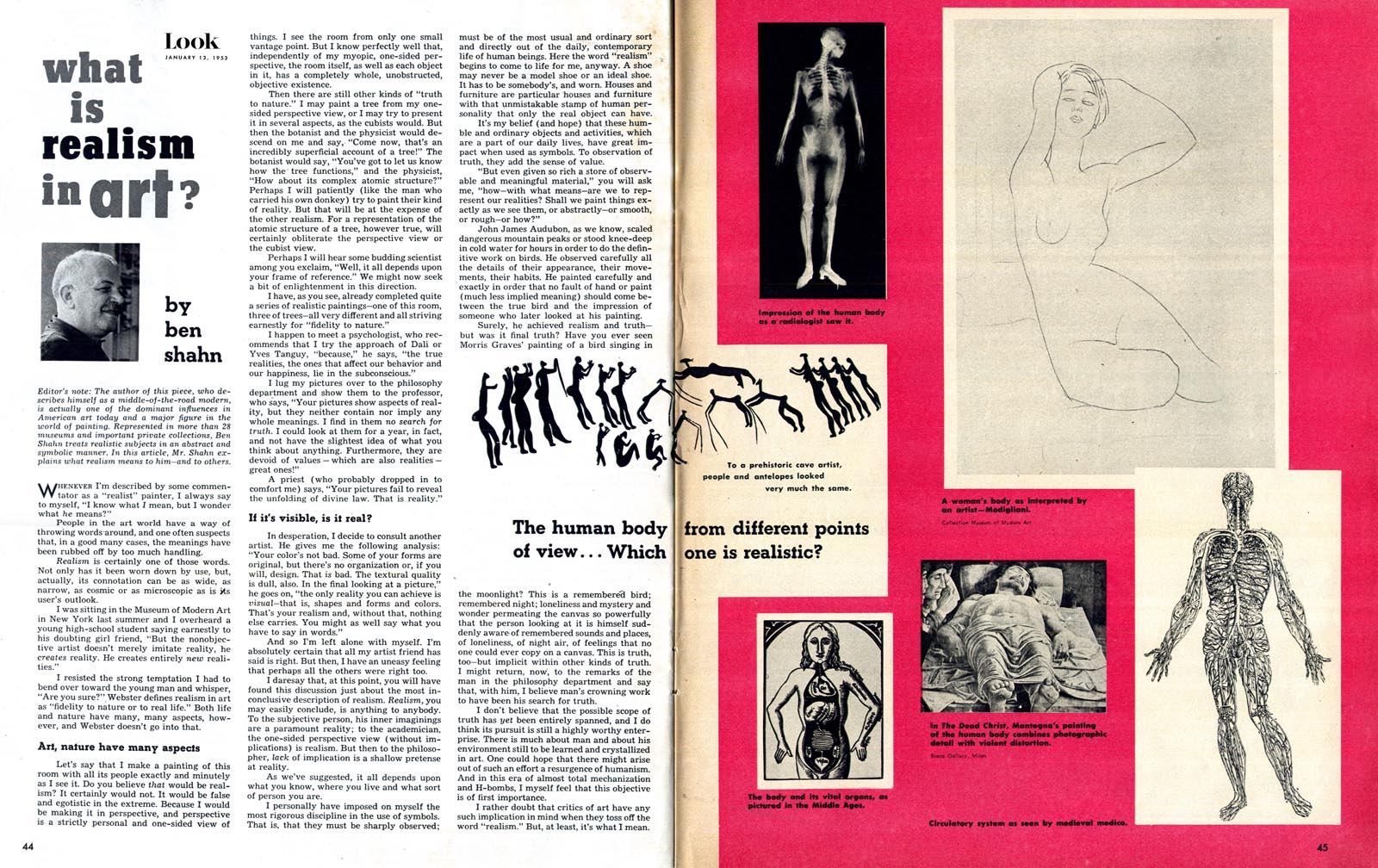

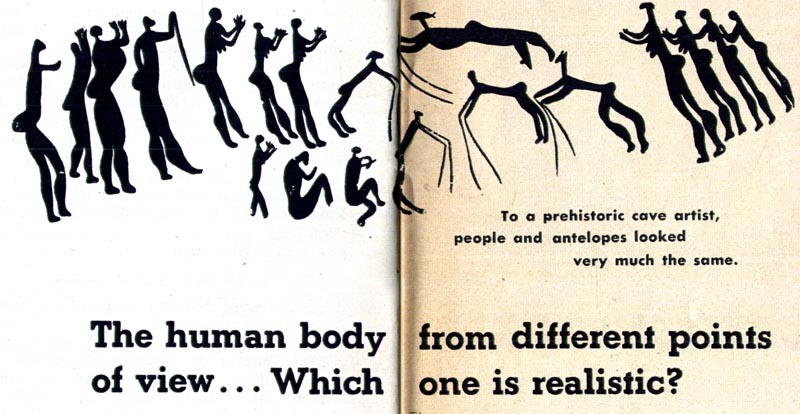

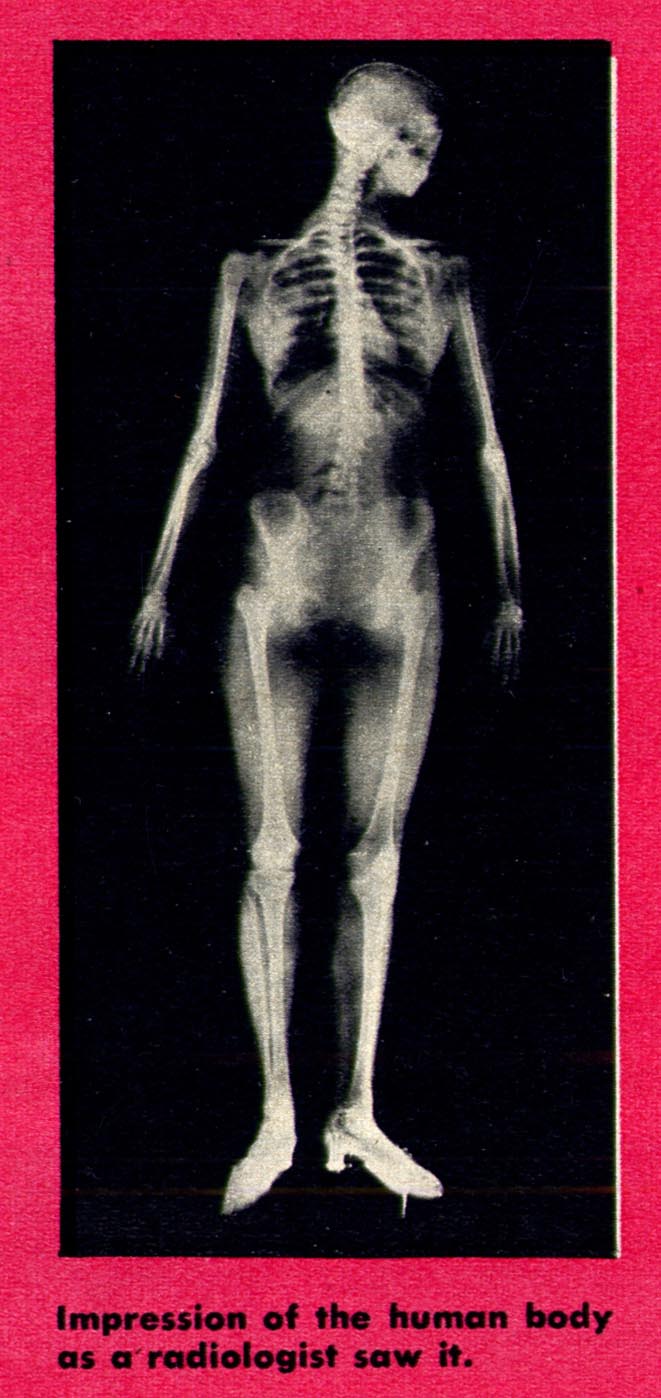

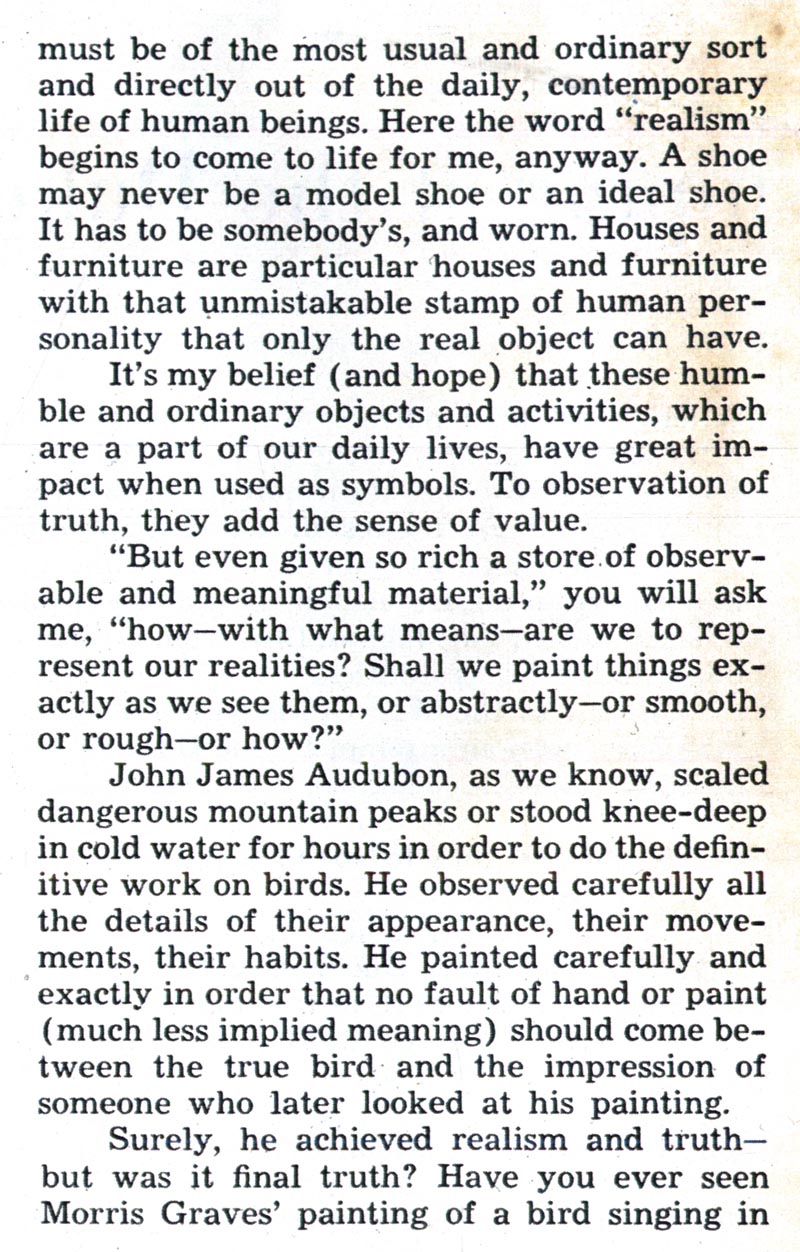

Later that same year Ben Shahn wrote an article in Look magazine wherein he challenged the accepted definition of what qualifies as "realism."

As requested by one reader, here is that article in its entirety. I think it conclusively describes Shahn's position on the subject of realism.

To summarize I'll quote Bill Koeb from the previous Ben Shahn post's comment section: "Before there were lenses, and long before there were cameras, what was considered "real" was very different. Realism is what you draw, not how you draw."

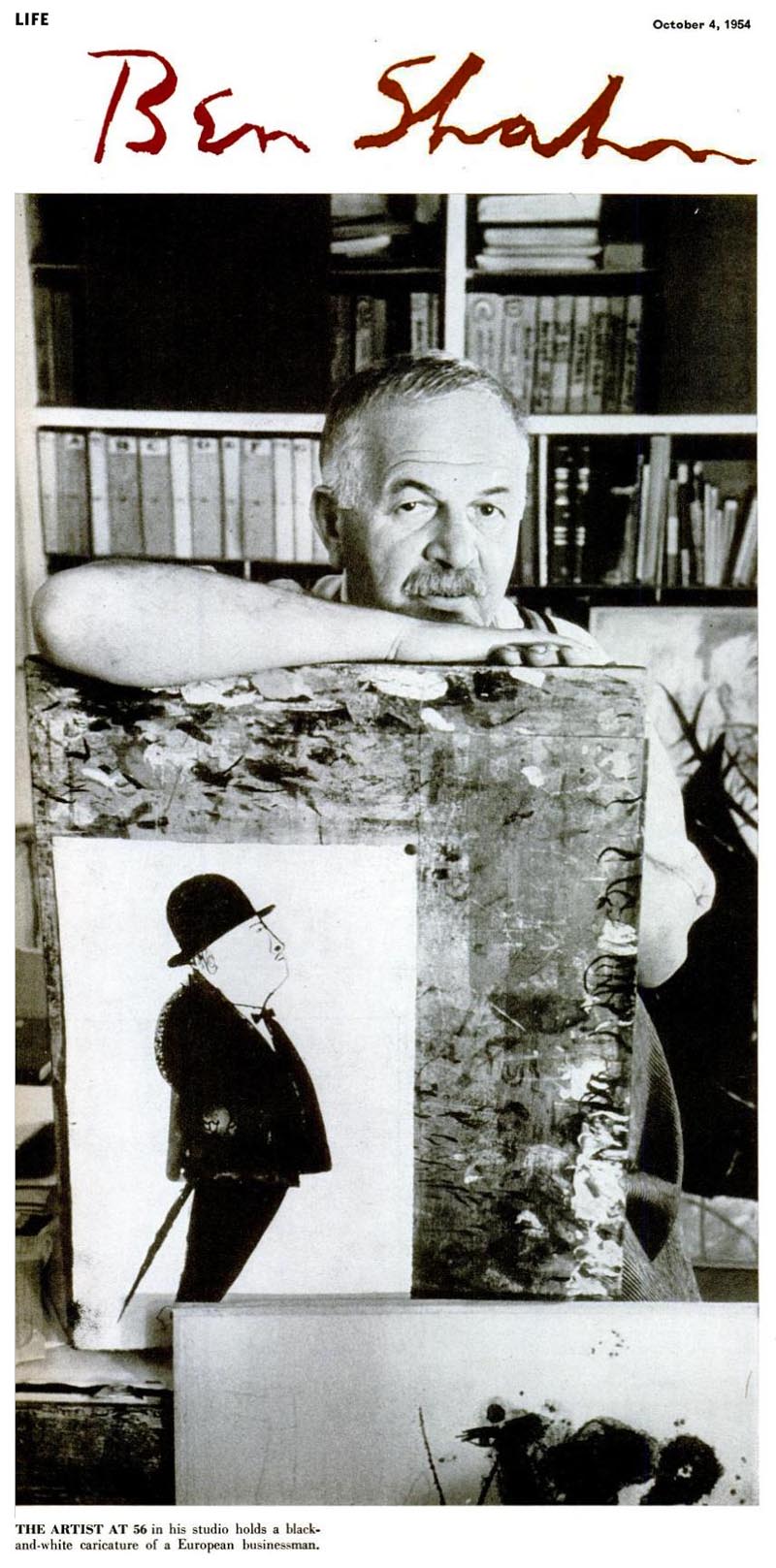

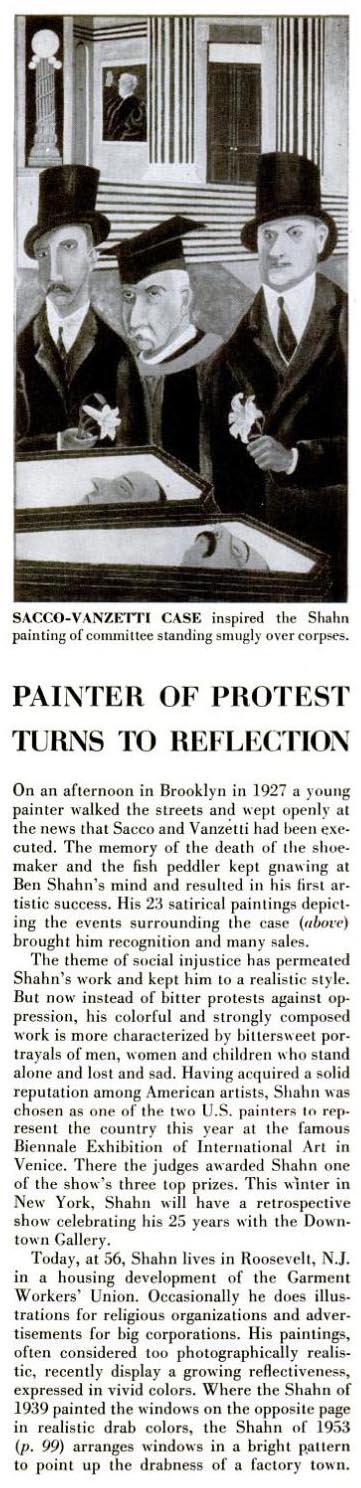

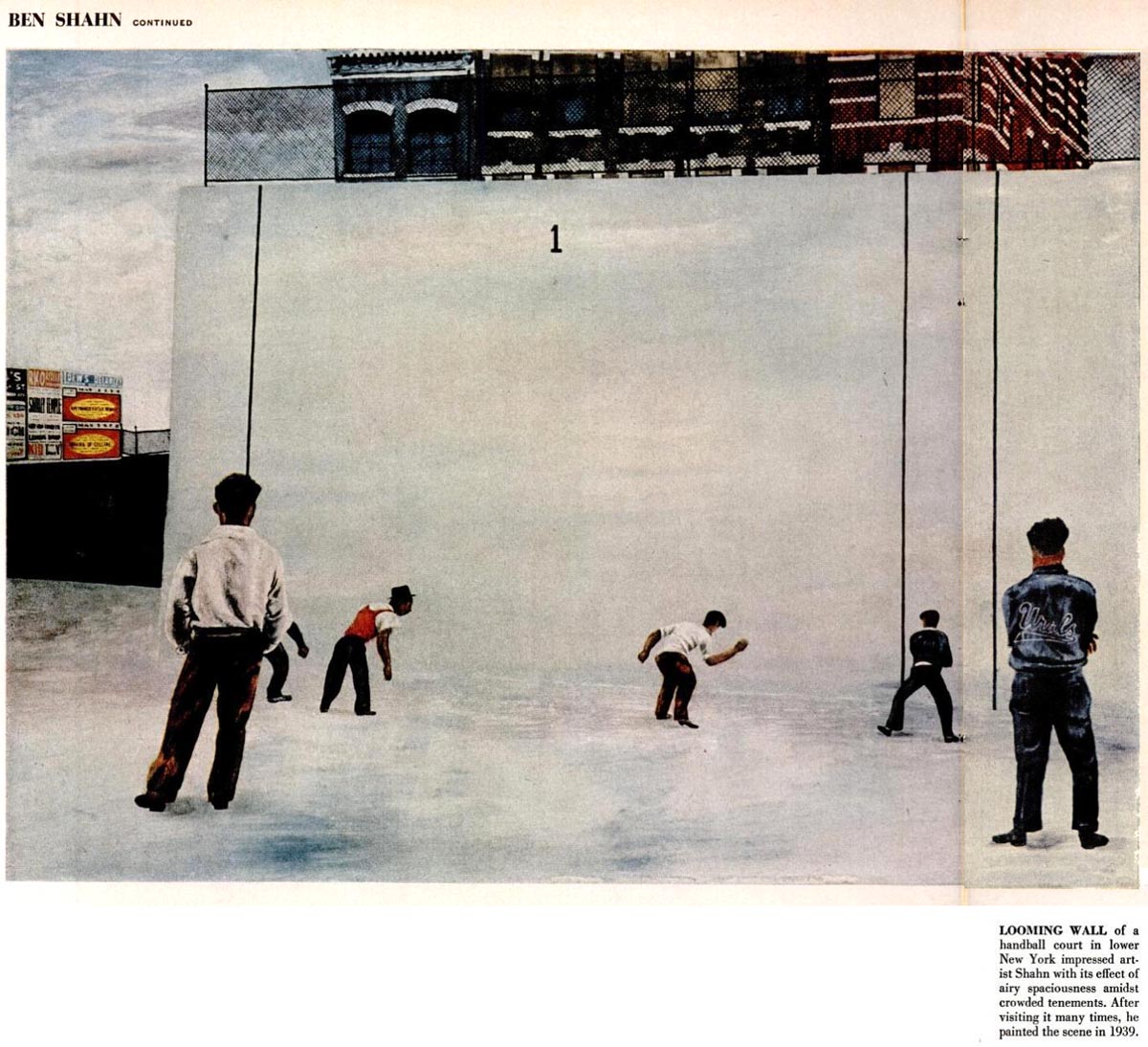

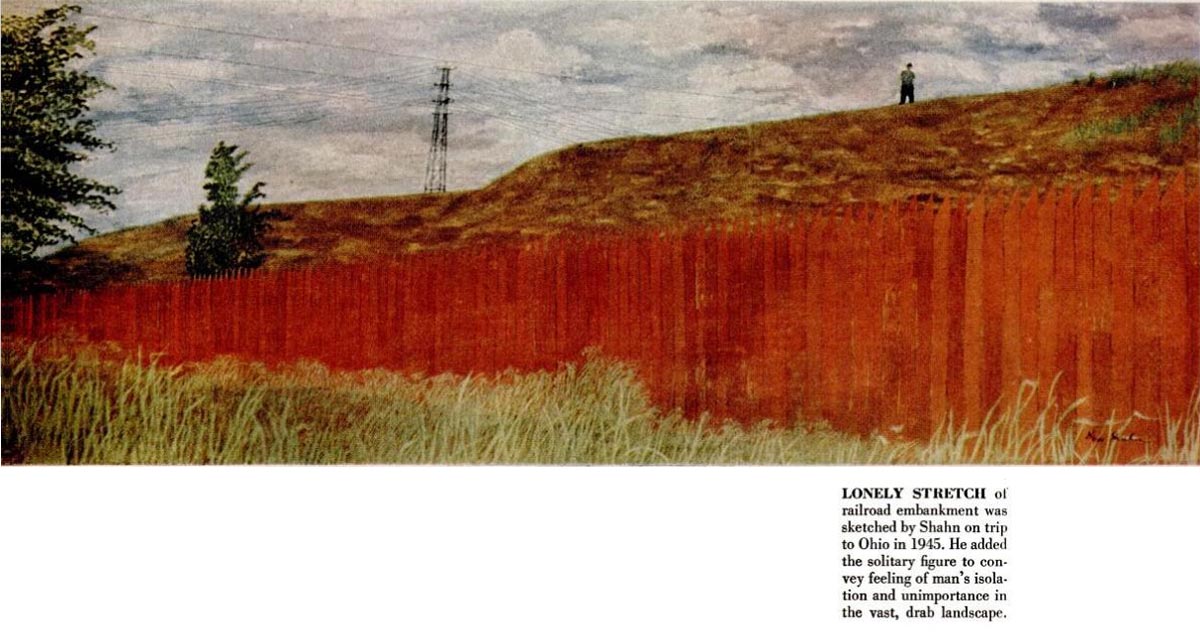

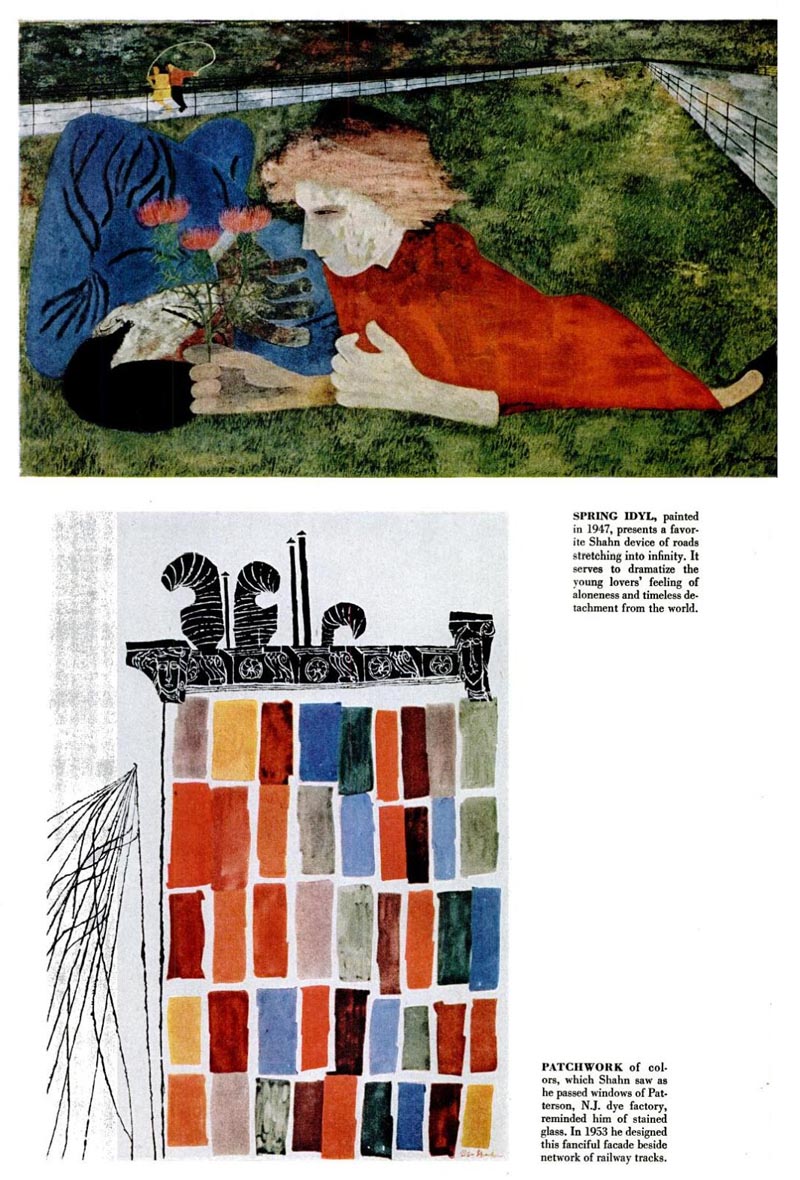

The following year, in Life magazine, Shahn's work was the subject of a major multi-page, full-colour article. If there was any doubt that Ben Shahn was a driving force in American art at that time, the glowing description of Shahn stature in both the Look and Life magazine articles should put them to rest.

I find it particularly amusing that Shahn's work is described as "too photographically realistic"!

Readers who participated in last week's discussion on Ben Shahn shared so many interesting perspectives. Here are a few more that came to me via personal emails -- and then a few thoughts of my own...

Anita Virgil, whom I quoted in last week's Ben Shahn post sent this note:

"What a fantastic writeup on Ben Shahn you give your readers! But I must address those Doubting Thomases out there who would denigrate or question Shahn’s different approach to expressing emotion via design and utter simplicity, I refer them to his own words from his classic, The Shape of Content, (Vintage Book, 1957) -- a must for every artistic individual to absorb."

"They appear in his section “On Nonconformity” p. 88:"

“But it seems to be less obvious somehow that to create anything at all in any field, and especially anything of outstanding worth, requires nonconformity, or a want of satisfaction with things as they are. The creative person -- the nonconformist — may be in profound disagreement with the present way of things, or he may simply wish to add his views, to render a personal account of matters.”

Contrasting that viewpoint, Tom Watson sent the following:

"Your Ben Shahn post fired up an interesting and varied viewpoint on his influence and the '50s, '60s illustration scene. It was quite controversial even when I was in art school. Ben Shahn was either loved and embraced or hated and scorned. I think his simplicity of composition and unusual point of view in these examples are worthy of the influence they generated, but some of his stuff was too crude and primitive looking for my personal taste in illustration technique. IMO there needed to be and was a separation between fine arts and illustration, even though they began spilling over into each other's territory. Illustration required some restriction and control in order to communicate to all targeted viewers."

At least one commenter from last week would counter Tom's assertions by saying that Shahn was many things - but he was not an illustrator - therefore he was not bound by the implied standards of professional conduct expected of the commercial artist. Personally, I reject the notion that Shahn was not an illustrator (and if he was, so what?).

As a visual communicator, the illustrator's job is to use his creativity to solve a client's communications challenges. That process often means undertaking work where one's own creativity takes a back seat to the client's needs and wishes. Although I'm sure Ben Shahn was selective about many of the assignments he chose to work on, he was not above doing work that asked little more of him creatively than his distinctive style.

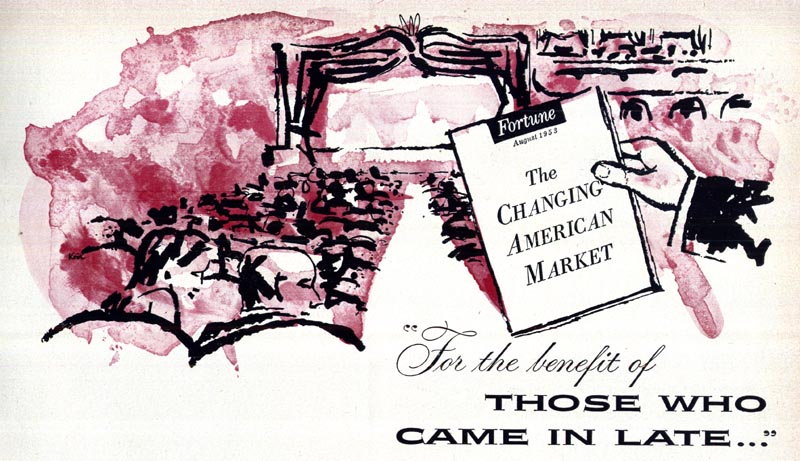

This ad for Fortune magazine's subscription page, for instance...

... or this article about business trends in paperback publishing...

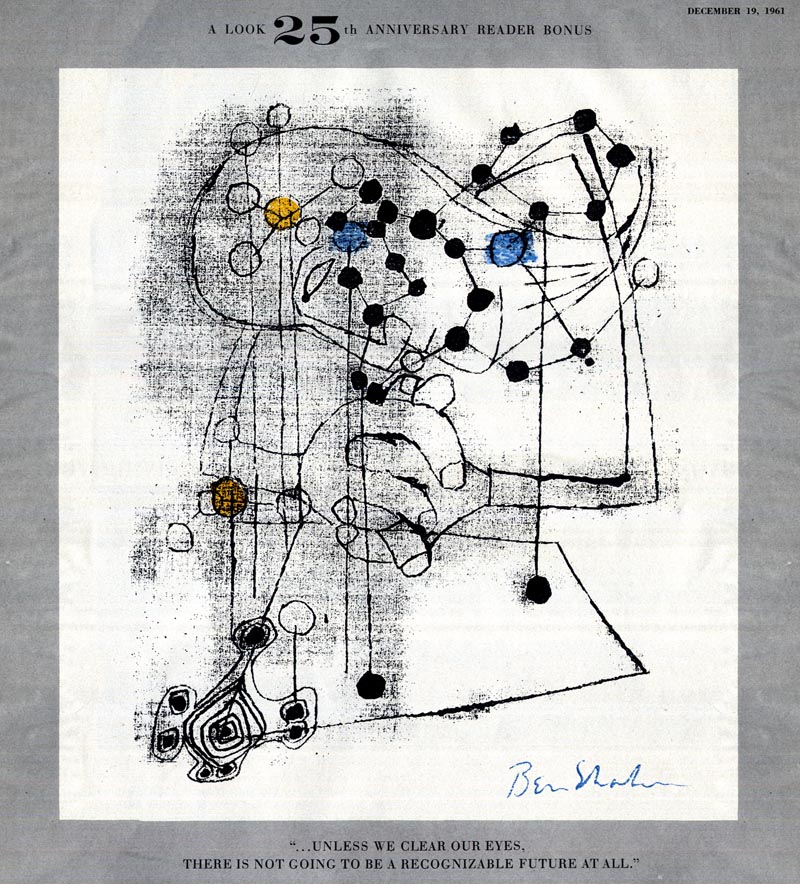

... or this DPS ad for the State of Israel, all of which really asked nothing more of Shahn than to decorate the page with appropriate illustrations in his distinctive style.

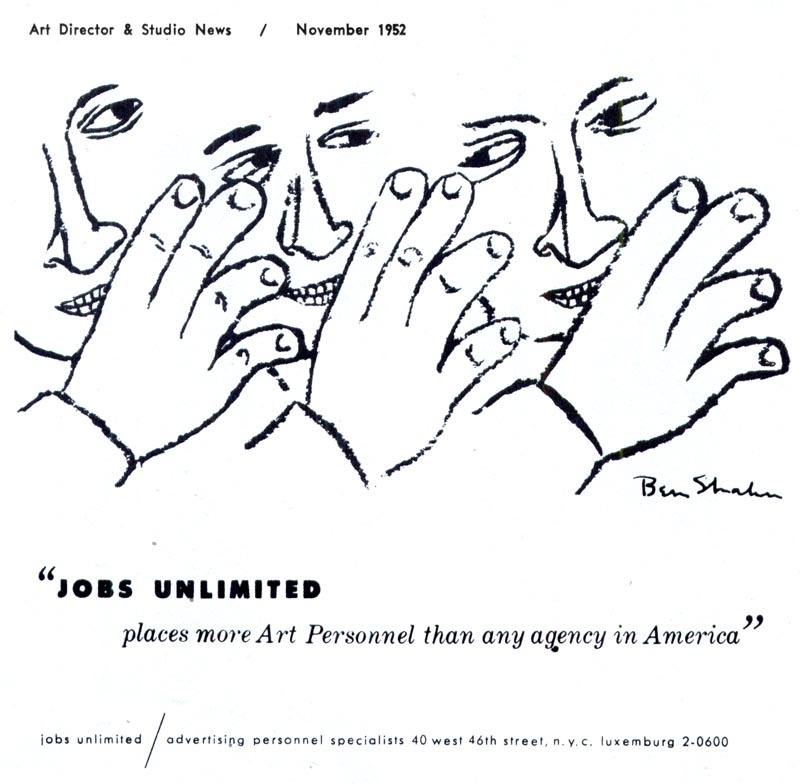

Shahn's work appeared regularly in trade publication ads for the '50s graphic arts service, Jobs Unlimited, suggesting his relationship with the graphic arts community - the commercial art community - was a sincere one.*

Just a few examples of how Ben Shahn was perfectly willing to provide professional service for payment as a journeyman illustrator and, in so doing, he demonstrated a realistic attitude about his role as a visual communicator (as well as his own brand of stylistic 'realism').

Its a complex subject - and as with so many other aspects of art and picture-making, one that's hard to quantify or to draw definitive conclusions about.

Personally, I believe Ben Shahn 'got' real... the question remains, do you?

* Thanks to Heritage Auctions for the use of the first two scans in today's post.

* Ben Shahn was posthumously inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame in 1994.

0 comments:

Post a Comment