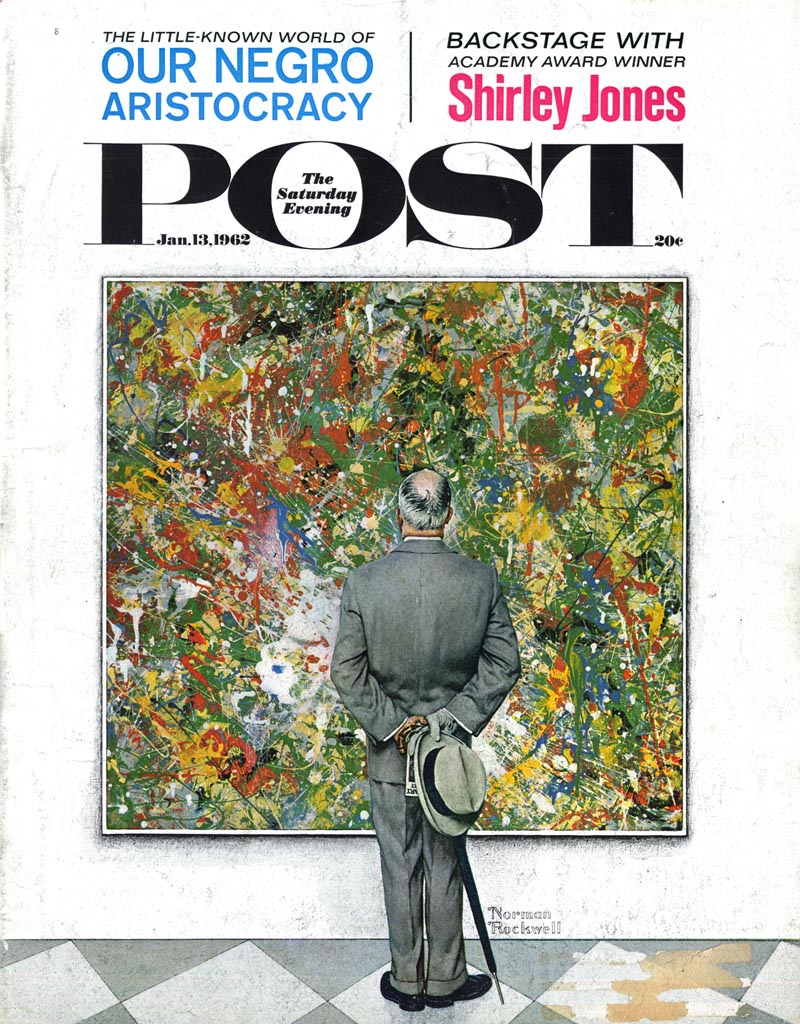

Sounds rather like the thinking of the traditionalist, Doesn't it? But, Weaver continues, "Mine was no longer the era of Norman Rockwell, where everything was easy, obvious, and on the surface.The kinds of stories I illustrated back in those days were rather complicated. I had to find ways to draw and paint that would match the abstract complexities of the writing. Magazines like Psychology Today were publishing articles about complex ideas; they needed conceptual artwork."

"I don't even remember ever reading anything in the Saturday Evening Post - I'd just look at the pictures - but I doubt the articles were very taxing on the brain. In their prime were the Cooper Studio people, the Joe Bowlers and the Coby Whitmores and the Jon Whitcombs. I remember liking Al Parker more than the others, although he certainly did that type of cutesy stuff. It was the ponytail period in American culture."

In the 1959 New York Art Director's Annual, Austin Briggs wrote this message to his fellow graphic arts professionals:

"It is common to blame the low visual quality of most advertising on either clients or the public, but the art director must ultimately accept the responsibility for the job which passes his desk. The art directors who are represented in this book are esthetically and commercially successful because they gave their artists freedom and managed to work in freedom themselves."

"They were willing to experiment and take risks."

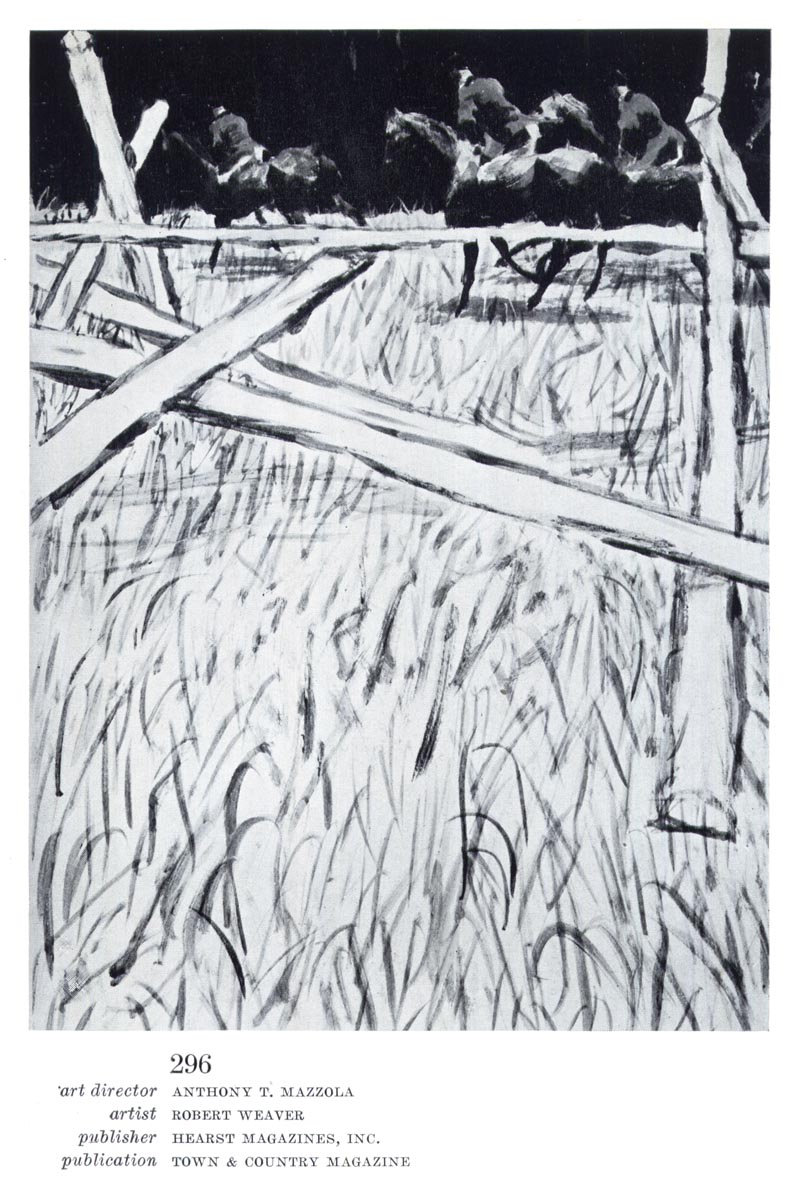

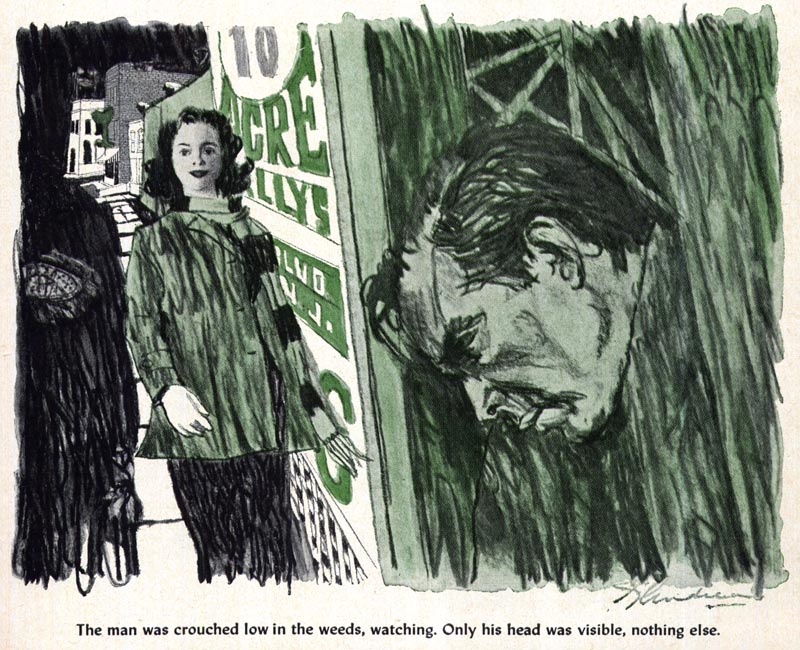

Robert Weaver's earliest accepted submission (below) to the NYAD Annual is included in the section directly behind Brigg's message.

The discussion this week around Weaver's art and philosophy have been passionate and polarized. His remarks have infuriated some readers and his work has been heavily criticized by others. Credit has been given almost grudgingly - and in a qualified manner. Weaver may be adored by one camp of artists - but he is nearly dismissed by another.

But dismiss him as you might as an elitist, a no-talent, a contributor to the "uglification of a great period in American art," as one person wrote, by the time Weaver was showcased in the September 1959 issue of American Artist, his influence on the look of then-contemporary illustration was becoming pronounced. Even established illustrators (including some of the industry's hottest young talents) were being influenced and attempting to incorporate a "Weaver look" in their work.

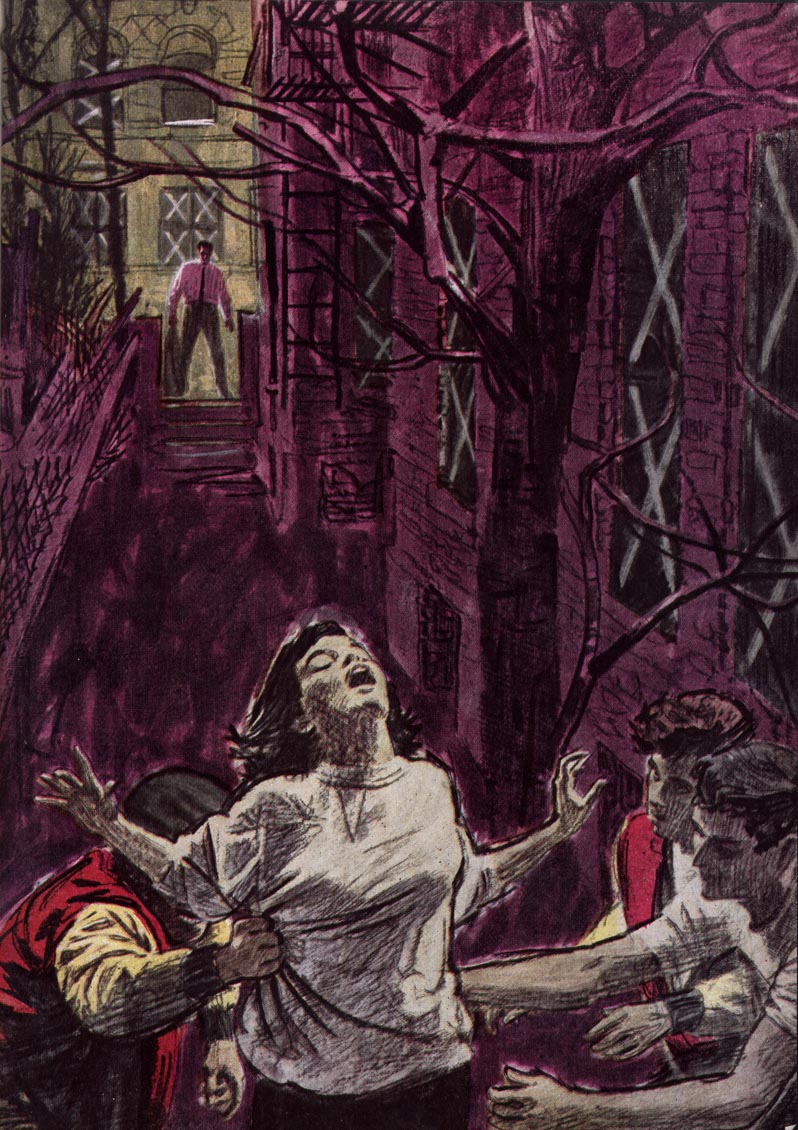

Consider the following examples (and I could easily show you many more):

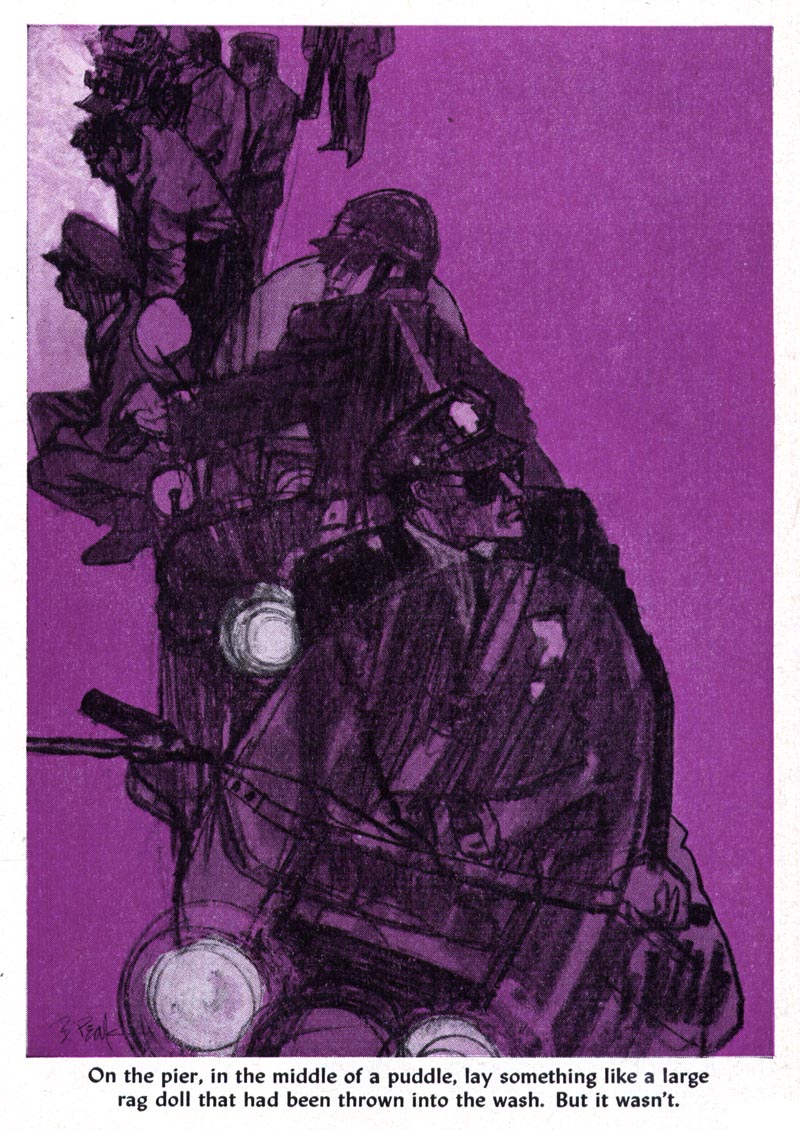

Bob Peak, 1962.

Bernie Fuchs, 1962.

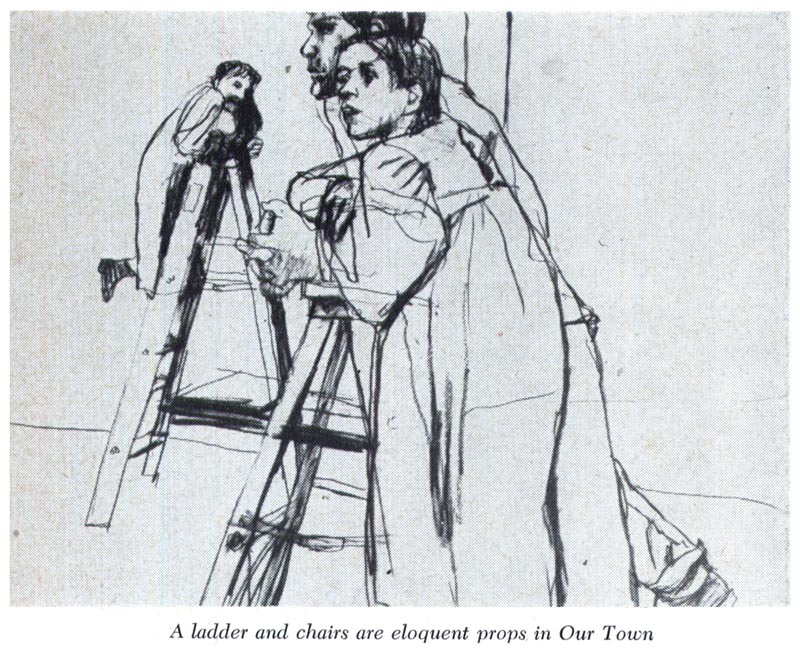

Bernie D'Andrea, 1962.

Mitchell Hooks, 1962.

Of course I'm not saying Weaver was the only avant-garde reshaping the look of illustration. Some others who were rising to prominence around the same time:

Phil Hays

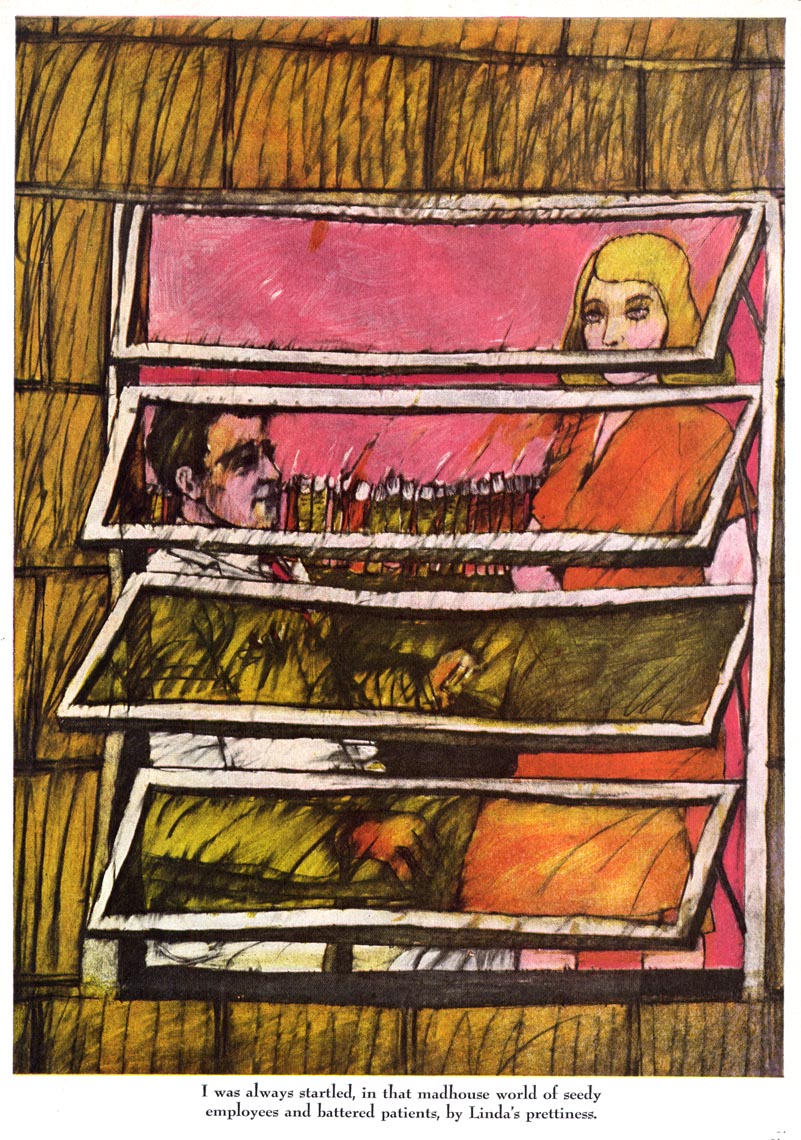

Tom Allen

Jack Potter

Cliff Condak.

There were, of course, many others.

Clever, open-minded illustrators willing to grow and experiment took what they saw as intriguing or appealing from this younger set and incorporated it into their own ever-evolving styles.

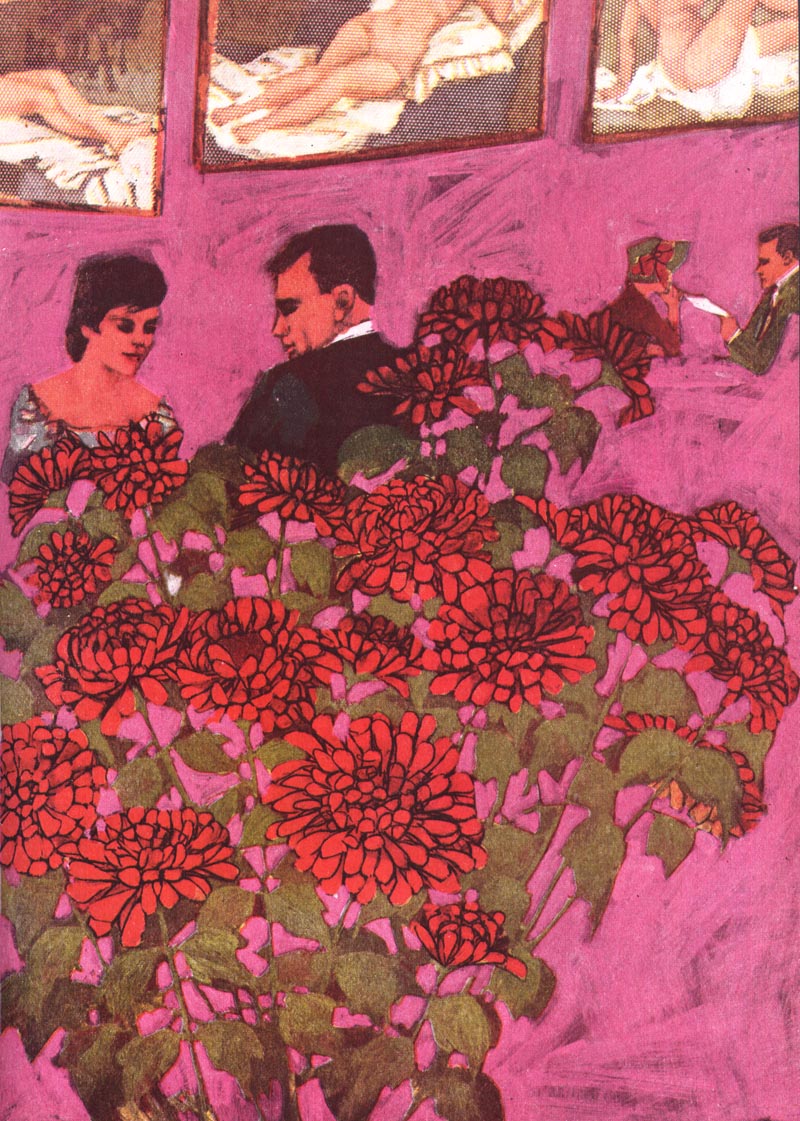

Al Parker, 1964.

The real genius of someone like Al Parker is that he understood the need for personal growth - but also the requirements of the marketplace.

The hurdle avante-garde illustrators face is the audience, the client and in many cases the graphic arts community itself is resistant to change. One commenter this week wrote, "was the public really looking for a wave of innovative "progressive" illustration approaches to seduce them into reading the magazines, or was it driven more by the Art/Creative Directors and illustrators like Weaver... illustrators that hated illustration as it was?"

According to Austin Briggs, what the public was looking for should not be the guiding principle of the graphic arts community. Briggs said its imperative that the art director be willing to take risks and experiment, to seek out and nurture the new and unusual - in spite of what the public may be comfortable with. It is to the benefit of the truly creative graphic arts professional to keep an open mind when confronted with the results of that risk-taking.

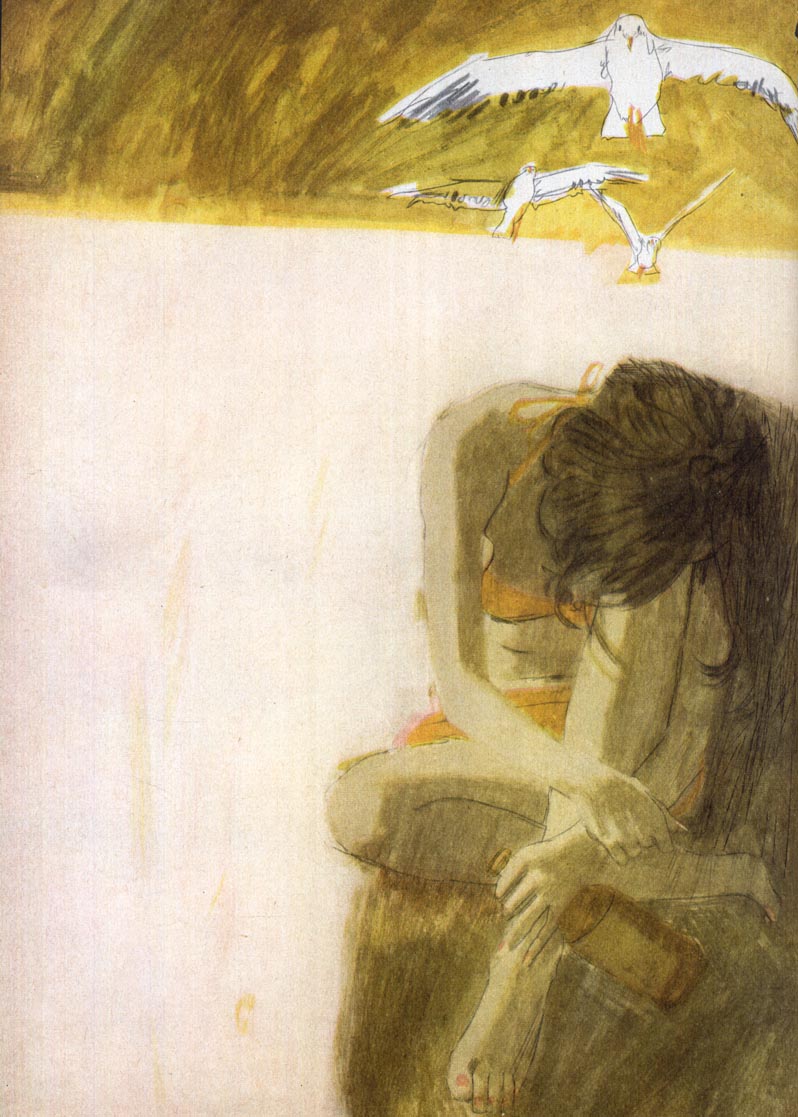

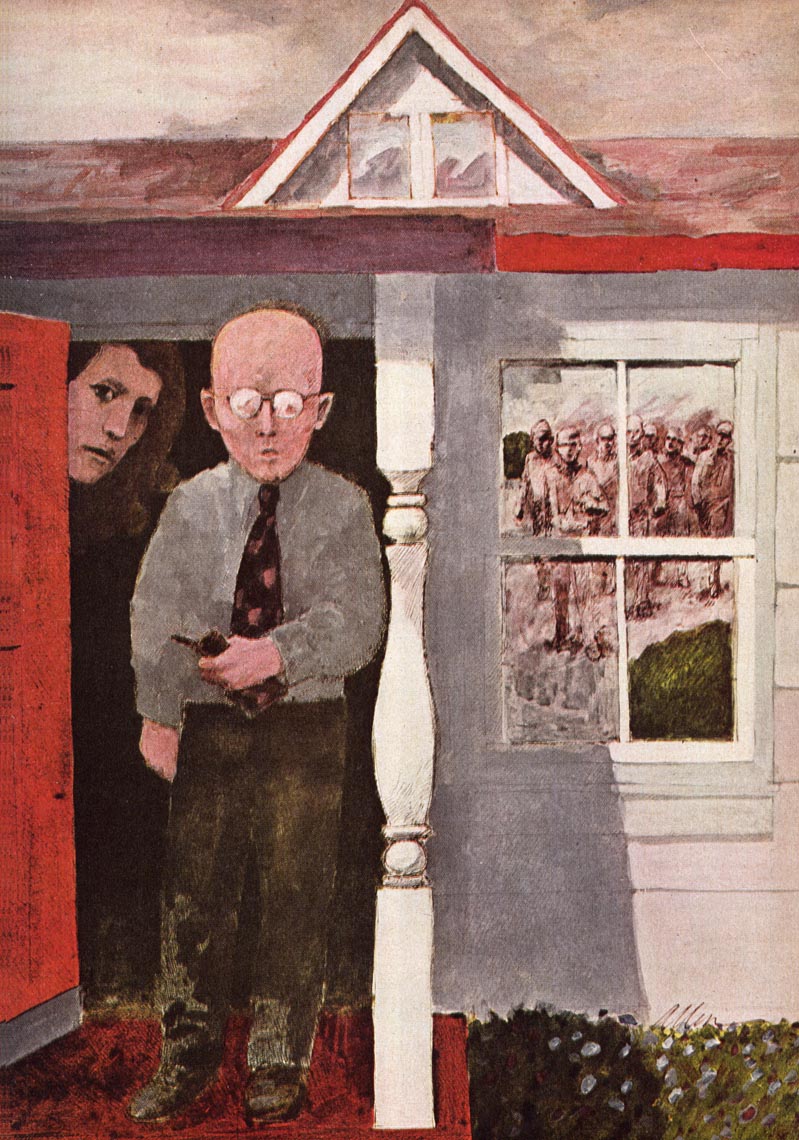

Robert Weaver, 1957.

Because it is the truly enlightened illustrator who sees the potential in what most others might dismiss - and considers how it might be incorporated into his own journey of artistic growth.

Austin Briggs, 1965.

* My Robert Weaver Flickr set.

0 comments:

Post a Comment